Category Archives: Gamification

Electrifying Education Through Gamification: Part 1 – The Challenge

Today I am starting a series of blog posts (and shortly, a series of YouTube videos) about how teachers can use game mechanics to make their lessons more engaging, motivating and memorable. These posts are based not only on research I’ve done into how gamification is used by educators, but also on how I use game-thinking and game mechanics in my own classroom when I teach game design and production at The Los Angeles Film School.

Today I am starting a series of blog posts (and shortly, a series of YouTube videos) about how teachers can use game mechanics to make their lessons more engaging, motivating and memorable. These posts are based not only on research I’ve done into how gamification is used by educators, but also on how I use game-thinking and game mechanics in my own classroom when I teach game design and production at The Los Angeles Film School.

Think back to the last great game you played. What made it great? You probably felt completely captivated while playing it. The minutes passed by in a blur; you were utterly absorbed and your full attention was devoted to the task at hand. This state of energized focus is what game designers call “flow”. Psychology Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi created a model, known as the “flow channel,” to describe the environment where skill and difficulty increase just enough to ensure that an experience is neither frustrating nor boring. When game players reach a flow state, they are fully immersed in an experience, losing track of time and personal needs.

Is that how you would describe the students in a typical classroom? Probably not. Many kids think of school as it’s depicted in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. To these students, school is boring and demotivating, when it should be exhilirating and engaging. What is it that traditional classrooms are doing wrong?

According to MIT, students remember only 10 percent of what they read, 20 percent of what they hear, and 50 percent of what they see demonstrated. But when students take an active role in their education, such when participating in a learning game or a virtual world, the retention rates skyrocket to 90 percent. Now, as any parent can tell you, most kids see homework as an unpleasant chore yet will happily toil for many hours grinding through quests in World of Warcraft and building elaborate structures in Minecraft. What makes “game work” more engaging than schoolwork?

One distinction is that schools typically reward students for compliance, thoroughness, and punctuality, whereas games reward players for experimentation, persistence, and play. The traditional educational model is passive and linear: the student sits at a desk and listens to a lecture; in a game, the experience is action-based and non-linear. If a student is struggling with a school subject, he is held back; however, when a player struggles with an obstacle, the game allows him to continue to try new strategies. There is little penalty for failure in a game, encouraging players to experiment.

In fact, failure itself serves as a learning tool: when players fail in a game, they acquire new knowledge and develop better skills. Such knowledge and skills become a resource for players, and the more players know, the better they become at playing the game. Game designer Raph Koster, author of A Theory of Fun, theorizes this process of constant learning is actually what makes games fun.

More and more educators are taking note that well designed games represent the best of learning design. Games are made of several design elements and work according to specific techniques. Games start easy and ramp up the difficulty level in such a way that players gain skills as they progress toward mastery. Games also provide models of desired behavior and give targeted feedback to direct players towards emulating that behavior. Game players regularly exhibit persistence, risk-taking, attention to detail, and problem solving — all behaviors that ideally would be regularly demonstrated in school.

How do we turn this game behavior into school behavior? That’s where gamfication comes in.

Gamification is the process of using a playful approach and game mechanics to engage people and solve problems. It’s purpose is to find out which of these elements and techniques should be used and how they should be used in non-game contexts. The final goal is to get people feel the deep levels of engagement experienced in games by approaching a flow state.

Gamification seeks to harness human motivation based on the premise that people play games because games are intrinsically rewarding and engaging. Although inventor and programmer Nick Pelling first coined the term in 2002, the concept has been in use for decades.

The boy scouts have long used merit badges to recognize a scout’s accomplishments in areas such as camping, electronics, and even game design, much in the same way that games now award achievements for players to display. Businesses use game-like techniques such as trading stamps, loyalty programs, and celebrations for the “one millionth customer” to encourage customer retention. Even the paying of taxes has been gamified through state lotteries.

But what would we do need to do to gamiify education? After all, schools already use several game-like elements. Students get points for completing assignments correctly. These points translate to achievements in the form of letter grades. Students are rewarded for desired behaviors and punished for undesirable ones using grades as a reward system.

And if students perform well, they “level up” at the end of every academic year.

Given all this, it would seem that school should already be the ultimate gamified experience. However, too often the traditional school environment results in boredom, cheating, and dropping out. There is still something missing from this environment, something that allows video games to excel at engaging kids.

Here is my YouTube video presentation of the above post.

In next week’s blog post, I’ll look at some of the game mechanics that have been used successfully to boost student engagement.

Player Types and Game Mechanics

On Saturday evening I taught a session of my introductory game production class at the Los Angeles Film School. I don’t normally teach on Saturdays, but we postponed a Tuesday night class to the weekend because that night I had been invited to give a lecture about Gamification and Learning to an Educational Technology class art Loyola Marymount University. So, this was one of those times when work spilled over into the weekend.

On Saturday evening I taught a session of my introductory game production class at the Los Angeles Film School. I don’t normally teach on Saturdays, but we postponed a Tuesday night class to the weekend because that night I had been invited to give a lecture about Gamification and Learning to an Educational Technology class art Loyola Marymount University. So, this was one of those times when work spilled over into the weekend.

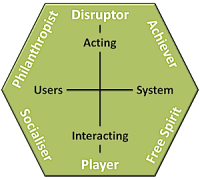

My Saturday lecture was about the human motivations that game designers tap into to make games engaging, and how designers should first determine what motivations they want the player experience to satisfy and then select devise the game mechanics that will create that play experience. (Novice game designers will often start planning a game based around game mechanics without consideration to the player experience, and that can lead to an unsatisfactory play aesthetic.)

For the lab following the lecture, I decided to have my LA Film School students do a gamification exercise similar to what I did for the LMU class earlier in the week. Not only did I think the exercise would be an good way to focus on the link between player motivations and game mechanics without the distraction of other game elements, but it gave me an excuse to use Andrzej Marczewski’s Gamification Inspiration Cards again.

I had my eight students that night break up into two teams of four, and each had to create a gamified system for solving one of several business problems I offered to them. Team One chose the task of training security guards to protect a building, and Team One selected the task of improving membership at a Health Club.

My student’s next step was to create a three-stage “User Journey” for their system’s uses. Team One decided to have their security guards get started by entering into a training session; once guards were able to attain an 80% score on a Standard Operating Procedure test, they would then be assigned to the lobby station, where they had to check the ID’s of people entering the building; and if the guards were able to catch three “ringers” who had false ID’s, the guards were promoted to making security rounds throughout the building.

My student’s next step was to create a three-stage “User Journey” for their system’s uses. Team One decided to have their security guards get started by entering into a training session; once guards were able to attain an 80% score on a Standard Operating Procedure test, they would then be assigned to the lobby station, where they had to check the ID’s of people entering the building; and if the guards were able to catch three “ringers” who had false ID’s, the guards were promoted to making security rounds throughout the building.

Team One elected to pursue Players, who are motivated by rewards. This is the gamified system they devised:

- Onboarding: New guards would take a series of tests on Standard Operating Procedures. They would receive achievement badges for answering various categories of questions correctly, and for each badge they earned, they could enter a lottery for winning prizes. If the trainees answered 80% of their test questions properly, they would move on to the next phase.

- Habit Building: After passing training, guards would be stationed in the lobby, where they would check employee ID’s. However, to test the guards’ diligence, “ringers” would occasionally arrive with false ID’s. The narrative provided to the guards that these were Ninjas who were trying to infiltrate the building. Guards who spotted the “Ninjas” with the false ID’s would be recognized on a leaderboard, and if they spotted 3 Ninjas, they would move on to the final phase.

- Mastery: Guards who graduated from the lobby station were assigned to patrol the building. They worked under a time limit mechanic for completing their rounds, and if they did, they would receive rewards, such as vacation time.

Team Two created a User Journey in which health club members were on-onboarded by filling out a membership form; they then developed the habit of visiting the health club through incentives for using the basic equipment; and when they achieved mastery, they were able to use the advanced equipment.

Team Two created a User Journey in which health club members were on-onboarded by filling out a membership form; they then developed the habit of visiting the health club through incentives for using the basic equipment; and when they achieved mastery, they were able to use the advanced equipment.

Team Two elected to pursue Achievers, who are motivated by Mastery. Achievers are looking to learn new things and improve themselves; they want challenges to overcome. Here is the gamified system they devised:

- Onboarding: New customers would be recruited through signposting via advertising. Once they come into the location, they would be shown tutorials about using the equipment.

- Habit Building: After signing, new customers would be allowed to use the Basic exercise equipment. As they gained experience with the equipment, they would gain points and level up to new ranks. Upon receiving a certain rank, they would move on to the final stage.

- Mastery: Customers who achieved mastery with the Basic equipment would be allowed to use Expert equipment. They would earn achievement badges for repeated use of categories of equipment, but if they failed to come into the club regularly, they would lose the right to use the Expert equipment and have to go back to the Basic equipment until they regained their rank.

Team One elected to have a single spokesman to “pitch” their gamification proposal to me, whereas Team One presented their proposal as a team effort. However, both did an excellent job and earned a full 100% grade for the assignment, and I think they learned about the importance of finding the right game mechanics to motivate different types of players.

What impresses me most about this assignment is that even though they are Game Production (and not Business or Marketing) students, my students always seem to enjoy gamifying a business problem. But perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised. After all, gamification is all about finding the fun in a non-game activity.