Blog Archives

How James Bond Influenced My Career

Last week I wrote about the pervasive influence that Star Trek has had on my life and career. With the twenty-fourth James Bond film Spectre debuting last weekend, this week I’m writing about how the James Bond films impacted me. While this creative franchise didn’t have quite the same degree of influence on me that Star Trek and Lord of the Rings did, it still was one of the three primary pop culture influences on my childhood.

Last week I wrote about the pervasive influence that Star Trek has had on my life and career. With the twenty-fourth James Bond film Spectre debuting last weekend, this week I’m writing about how the James Bond films impacted me. While this creative franchise didn’t have quite the same degree of influence on me that Star Trek and Lord of the Rings did, it still was one of the three primary pop culture influences on my childhood.

Because the Bond films are not child-friendly films, their impact on me was indirect during my early childhood in that they influenced many of the shows I did watch. James Bond creator Ian Fleming himself helped develop the show The Man from U.N.C.L.E., which followed the adventures of an American and Russian secret agent, played by Robert Vaughn and David McCallum, who worked for a secret international counter espionage and law and enforcement agency. I Spy, starring Robert Culp and Bill Cosby, used exotic international locations to emulate the James Bond films. An especially favorite show of mine was the spy spoof Get Smart, starring Don Adams as Maxwell Smart, Agent 86, who was a cross between James Bond and Inspector Clouseau. One recurring gag on the show was that telephones are concealed in over objects a necktie, comb, watch, a clock, and most frequently, Max’s shoe phone, which he has to take off to answer calls from his superior.

Because the Bond films are not child-friendly films, their impact on me was indirect during my early childhood in that they influenced many of the shows I did watch. James Bond creator Ian Fleming himself helped develop the show The Man from U.N.C.L.E., which followed the adventures of an American and Russian secret agent, played by Robert Vaughn and David McCallum, who worked for a secret international counter espionage and law and enforcement agency. I Spy, starring Robert Culp and Bill Cosby, used exotic international locations to emulate the James Bond films. An especially favorite show of mine was the spy spoof Get Smart, starring Don Adams as Maxwell Smart, Agent 86, who was a cross between James Bond and Inspector Clouseau. One recurring gag on the show was that telephones are concealed in over objects a necktie, comb, watch, a clock, and most frequently, Max’s shoe phone, which he has to take off to answer calls from his superior.

Spy adventures and secret agent gear comprised a lot of my make-believe play. I bought and studied books about how to make codes and ciphers, such as using lemon juice as “invisible ink” to send secret messages. I played with all sorts of secret agent toys such as radios and cameras that turned into “guns”; the Johnny Seven gun that had seven different weapons including a grenade launcher and anti-tank rocket; and the Secret Sam attaché case that featured not only a gun with silencer but also had a secret button on that fired a bullet out one side of the briefcase. With me playing with all those guns, you might think that I was a blood-thirsty little tyke, what actually fascinated me was the ingenuity of how they were designed, and there ability to transform from one thing to another — much like kids that grew up after me enjoyed Transformer toys.

Spy adventures and secret agent gear comprised a lot of my make-believe play. I bought and studied books about how to make codes and ciphers, such as using lemon juice as “invisible ink” to send secret messages. I played with all sorts of secret agent toys such as radios and cameras that turned into “guns”; the Johnny Seven gun that had seven different weapons including a grenade launcher and anti-tank rocket; and the Secret Sam attaché case that featured not only a gun with silencer but also had a secret button on that fired a bullet out one side of the briefcase. With me playing with all those guns, you might think that I was a blood-thirsty little tyke, what actually fascinated me was the ingenuity of how they were designed, and there ability to transform from one thing to another — much like kids that grew up after me enjoyed Transformer toys.

My favorite spy toy was a die-cast model of the Aston Martin DB5 from Goldfinger. Like the film car, this toy from Corgi featured retractable front-mounted machine guns, bullet-proof rear screen, revolving number plates, tire shredders, and best of all, a working ejector seat that would send the occupant flying out of the roof. Now, I had never actually seen a James Bond film at this point, but I have a vivid memory of my Dad calling me over to the television showing a scene of Q showing off the Aston Martin’s features to Bond.

My favorite spy toy was a die-cast model of the Aston Martin DB5 from Goldfinger. Like the film car, this toy from Corgi featured retractable front-mounted machine guns, bullet-proof rear screen, revolving number plates, tire shredders, and best of all, a working ejector seat that would send the occupant flying out of the roof. Now, I had never actually seen a James Bond film at this point, but I have a vivid memory of my Dad calling me over to the television showing a scene of Q showing off the Aston Martin’s features to Bond.

I didn’t actually see my first Bond film until I was 11-years-old, when my Dad took my brothers and I to see On Her Majesty’s Secret Service at the local movie theater. I didn’t know George Lazenby from Sean Connery at this point, so the opening scene where Lazenby’s Bond loses a fight and breaks the fourth wall by saying to the camera, “This never happened to the other fellow” was lost on me. I immediately loved the film for its clever gadgets, exotic locales, exciting action sequences, and supervillians with hidden lairs and elaborate plans for world domination. However, at that age, the sex (and sexism) was a bit over my head.

I didn’t actually see my first Bond film until I was 11-years-old, when my Dad took my brothers and I to see On Her Majesty’s Secret Service at the local movie theater. I didn’t know George Lazenby from Sean Connery at this point, so the opening scene where Lazenby’s Bond loses a fight and breaks the fourth wall by saying to the camera, “This never happened to the other fellow” was lost on me. I immediately loved the film for its clever gadgets, exotic locales, exciting action sequences, and supervillians with hidden lairs and elaborate plans for world domination. However, at that age, the sex (and sexism) was a bit over my head.

I caught up on all of previous Bond films that ABC would regularly broadcast on television, and although he wasn’t my first Bond, Connery became my favorite because of his suave and debonair approach to the character (which I later learned was due to director Terrence Young coaching the scruffy Connery in the ways of being dapper, witty, and cultured). Connery’s Bond was also as ruthless as he was charming, for he could just as easily slide a knife into a female adversary as he could make love to her to gain her loyalty.

I caught up on all of previous Bond films that ABC would regularly broadcast on television, and although he wasn’t my first Bond, Connery became my favorite because of his suave and debonair approach to the character (which I later learned was due to director Terrence Young coaching the scruffy Connery in the ways of being dapper, witty, and cultured). Connery’s Bond was also as ruthless as he was charming, for he could just as easily slide a knife into a female adversary as he could make love to her to gain her loyalty.

During my teenage years, my best friend, Andrew Weber, and I would ride our bicycles together to the movie theater to catch the latest Bond film. By this time, Roger Moore had taken over the role after Connery’s departure. Although all Bond films are ridiculous to some degree, I did not like Moore’s approach to the character, which Connery said differed from his in that “I would leave the scene laughing, while Roger would enter the scene laughing”. I wanted my Bond to be a bit more serious when saving the world.

During my teenage years, my best friend, Andrew Weber, and I would ride our bicycles together to the movie theater to catch the latest Bond film. By this time, Roger Moore had taken over the role after Connery’s departure. Although all Bond films are ridiculous to some degree, I did not like Moore’s approach to the character, which Connery said differed from his in that “I would leave the scene laughing, while Roger would enter the scene laughing”. I wanted my Bond to be a bit more serious when saving the world.

I found the grittiness I was wanted by reading the original Ian Fleming novels, in which the literary Bond was not as handsome or unflappable as the film versions. I was put off by some of the racial insensitive of the books, but we were reading Huckleberry Finn at the same time in high school, so I took Fleming’s use of the “N-” word as a sign of another, less enlighten time. Ian Fleming saw himself as part of an elite class, and he undoubtedly saw everyone who was not a member of British upper society as beneath him.

I found the grittiness I was wanted by reading the original Ian Fleming novels, in which the literary Bond was not as handsome or unflappable as the film versions. I was put off by some of the racial insensitive of the books, but we were reading Huckleberry Finn at the same time in high school, so I took Fleming’s use of the “N-” word as a sign of another, less enlighten time. Ian Fleming saw himself as part of an elite class, and he undoubtedly saw everyone who was not a member of British upper society as beneath him.

My reading then turned to American spy stories. Watergate was happening at the time, and so I read a (very mediocre) spy novel written by Watergate conspirator and ex-CIA agent E. Howard Hunt. When I was older, I started reading Tom Clancy’s techno-thriller books, most of which centered around CIA intelligence officer Jack Ryan. Although I greatly enjoyed the technically details of his espionage and military science storylines set during and after the Cold War, I eventually grew tired of Clancy’s heavy-handed conservative views in which all the right-leaning characters were pure and good and the left-leaning characters were flawed or evil.

My reading then turned to American spy stories. Watergate was happening at the time, and so I read a (very mediocre) spy novel written by Watergate conspirator and ex-CIA agent E. Howard Hunt. When I was older, I started reading Tom Clancy’s techno-thriller books, most of which centered around CIA intelligence officer Jack Ryan. Although I greatly enjoyed the technically details of his espionage and military science storylines set during and after the Cold War, I eventually grew tired of Clancy’s heavy-handed conservative views in which all the right-leaning characters were pure and good and the left-leaning characters were flawed or evil.

I preferred my fiction to be more thought-provoking, and our of all the spy-themed movies, books, and television shows that most captured my interests was The Prisoner, a 17-episode British television eerie first broadcast in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s but rebroadcast on PBS while I was attending college a decade later. The series follows a British former secret agent who is abducted and held prisoner in a mysterious coastal village resort where his captors try to find out why he abruptly resigned from his job. Although the show was outwardly a spy thriller, what appealed to me was its surreal settings and 1960s countercultural themes about maintaining one’s individuality despite society’s pressure to conform.

I preferred my fiction to be more thought-provoking, and our of all the spy-themed movies, books, and television shows that most captured my interests was The Prisoner, a 17-episode British television eerie first broadcast in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s but rebroadcast on PBS while I was attending college a decade later. The series follows a British former secret agent who is abducted and held prisoner in a mysterious coastal village resort where his captors try to find out why he abruptly resigned from his job. Although the show was outwardly a spy thriller, what appealed to me was its surreal settings and 1960s countercultural themes about maintaining one’s individuality despite society’s pressure to conform.

I was so enthralled with the show that when I joined Edu-Ware Services as a game designer/programmer after graduating college, I convinced my boss to let me develop a game based on the show. Over a six-week period I designed the game as I was programming it, devising situations based not just based on the show’s themes and spy genre tropes, but also incorporating famous experiments, like the Milgram experiment, that I learned about in a college psychology class.

I was so enthralled with the show that when I joined Edu-Ware Services as a game designer/programmer after graduating college, I convinced my boss to let me develop a game based on the show. Over a six-week period I designed the game as I was programming it, devising situations based not just based on the show’s themes and spy genre tropes, but also incorporating famous experiments, like the Milgram experiment, that I learned about in a college psychology class.

Because we didn’t acquire a license to The Prisoner, my game was only loosely based on the show but incorporated its themes about the loss of individuality in a technological, controlling society. The player’s role is that of an intelligence agent who has resigned from his job for reasons known only to himself, and who has been abducted to an isolated island community that seems designed to be his own personal prison. The island’s authorities use coercion, disorientation, deception, and frustration to learn why the player has resigned, and every character, location, and apparent escape route seem to be part of a grand scheme to trick the player into revealing a code number representing the prisoner’s reason for resigning.

Because we didn’t acquire a license to The Prisoner, my game was only loosely based on the show but incorporated its themes about the loss of individuality in a technological, controlling society. The player’s role is that of an intelligence agent who has resigned from his job for reasons known only to himself, and who has been abducted to an isolated island community that seems designed to be his own personal prison. The island’s authorities use coercion, disorientation, deception, and frustration to learn why the player has resigned, and every character, location, and apparent escape route seem to be part of a grand scheme to trick the player into revealing a code number representing the prisoner’s reason for resigning.

The game turned out to be my greatest personal creative achievement. I programmed a text parser so that the player could communicate in English with his captors, which one game reviewer described as “the best example of artificial intelligence seen in or outside of any game.” One of my more nefarious attempts to get the player to reveal the reasons why he resigned was a simulated game crash which includes the error message “Syntax error in line ###”, where the line number is the player’s resignation code. I also had game occasionally break the fourth wall by acknowledging that a game is being played and the player has chosen to imprison himself by agreeing willingly to play the game.

The game turned out to be my greatest personal creative achievement. I programmed a text parser so that the player could communicate in English with his captors, which one game reviewer described as “the best example of artificial intelligence seen in or outside of any game.” One of my more nefarious attempts to get the player to reveal the reasons why he resigned was a simulated game crash which includes the error message “Syntax error in line ###”, where the line number is the player’s resignation code. I also had game occasionally break the fourth wall by acknowledging that a game is being played and the player has chosen to imprison himself by agreeing willingly to play the game.

The game was both a financial and critical success, sufficiently so that I wrote a color graphics sequel called Prisoner 2 that was equally well-received. Unfortunately, that was the last opportunity I had to developed a spy-themed video game.

Still, my interest in the spy genre never waned, and Bond somehow always impacted my life, in addition to me watching the films through the Moore, Dalton, Brosnan and Craig years. During one trip to Las Vegas, I volunteered to go up on stage during a performance of Pat Collins, “The Hip Hypnotist”. She “hypnotized” me into believing I was James Bond, and so I pulled out an imaginary “gun”, leapt off the stage, grabbed an cocktail waitress by the arm, and escorted her off to safety.

Still, my interest in the spy genre never waned, and Bond somehow always impacted my life, in addition to me watching the films through the Moore, Dalton, Brosnan and Craig years. During one trip to Las Vegas, I volunteered to go up on stage during a performance of Pat Collins, “The Hip Hypnotist”. She “hypnotized” me into believing I was James Bond, and so I pulled out an imaginary “gun”, leapt off the stage, grabbed an cocktail waitress by the arm, and escorted her off to safety.

I had another Bond encounter when I was working at Cyberdreams, producing the game Dark Seed II with H.R. Giger. Because I had my hands full designing another game, I brought on a freelance designer to work on the Giger game, and the person I hired was Raymond Benson, who had designed a number of text and graphic adventure games for Origin Systems, MicroProse, and Mindscape, including games based on the James Bond films A View To A Kill and Goldfinger. Raymond was also the author of the non-fiction book The James Bond Bedside Companion, which is an indispensable resource for Bond fans.

I had another Bond encounter when I was working at Cyberdreams, producing the game Dark Seed II with H.R. Giger. Because I had my hands full designing another game, I brought on a freelance designer to work on the Giger game, and the person I hired was Raymond Benson, who had designed a number of text and graphic adventure games for Origin Systems, MicroProse, and Mindscape, including games based on the James Bond films A View To A Kill and Goldfinger. Raymond was also the author of the non-fiction book The James Bond Bedside Companion, which is an indispensable resource for Bond fans.

In 1996, when official James Bond novelist John Gardner resigned from writing Bond books. Glidrose Publications hired Raymond to replace him. Raymond wound up writing six James Bond novels, three novelizations, and three short stories (he was the first writer after creator Ian Fleming to write a Bond short story). I, of course, read all of Raymond’s Bond works and am lucky enough to have several autographed copies of his novels, which occupy a treasured space in my library.

In 1996, when official James Bond novelist John Gardner resigned from writing Bond books. Glidrose Publications hired Raymond to replace him. Raymond wound up writing six James Bond novels, three novelizations, and three short stories (he was the first writer after creator Ian Fleming to write a Bond short story). I, of course, read all of Raymond’s Bond works and am lucky enough to have several autographed copies of his novels, which occupy a treasured space in my library.

Knowing of my mutual love for Bond, Raymond invited me to a James Bond convention in Los Angeles where he was appearing as a speaker and performer (in addition to being a phenomenal writer, Raymond is also a terrific pianist). After attending Raymond’s session, I saw my “first” Bond, George Lazenby, in person, along with Richard Kiel (“Jaws” from The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker) and Bruce Glover (“Mr. Wint” in Diamonds Are Forever). Raymond has since gone on to writing his own very successful mystery novels, and I try to see him whenever he is in town for a book signing or business meeting.

Knowing of my mutual love for Bond, Raymond invited me to a James Bond convention in Los Angeles where he was appearing as a speaker and performer (in addition to being a phenomenal writer, Raymond is also a terrific pianist). After attending Raymond’s session, I saw my “first” Bond, George Lazenby, in person, along with Richard Kiel (“Jaws” from The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker) and Bruce Glover (“Mr. Wint” in Diamonds Are Forever). Raymond has since gone on to writing his own very successful mystery novels, and I try to see him whenever he is in town for a book signing or business meeting.

As for my own spy adventures, although I never had an opportunity to work on any spy-themed videogames since The Prisoner and Prisoner 2, I did some work on a spy-themed live action game last year. Two entrepreneurs interested in staring up an Escape Room franchise hired me to design some scenarios for them, including a spy-themed scenario in which players find clues hidden in secret compartments and use them to break codes and solve other puzzles that will ultimately let escape from a locked room. It was great fun to work on, although the project never advanced past the design phase.

As for my own spy adventures, although I never had an opportunity to work on any spy-themed videogames since The Prisoner and Prisoner 2, I did some work on a spy-themed live action game last year. Two entrepreneurs interested in staring up an Escape Room franchise hired me to design some scenarios for them, including a spy-themed scenario in which players find clues hidden in secret compartments and use them to break codes and solve other puzzles that will ultimately let escape from a locked room. It was great fun to work on, although the project never advanced past the design phase.

I don’t know if I’ll ever get to work on an actual James Bond game, but I never expected Sean Connery to return to the role in Never Say Never Again or Eon Productions to hire a blonde-haired actor like Daniel Craig to play Bond, so maybe some day I’ll have an opportunity to virtually join Her Majesty’s Secret Service as an agent creating works rather than as a spy viewing them.

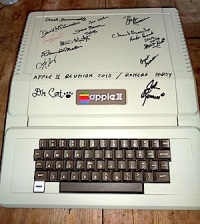

Remembering the fun of making games at the 2015 Apple ][ Reunion Party

For this week’s blog post I had planned to write about my experiences at E3, the Electronic Entertainment Expo, but then I received an invitation to attend an even more noteworthy event — a reunion at the home of Doom developer John Romero for many of us who had developed games for the Apple II computer. In addition to being a historic figure in game development himself, John has a deep love for the history of Apple II games. John’s first published game, Scout Search, appeared in the June 1984 issue of inCider, a popular Apple II magazine during the 1980s, and he went on to develop a number of Apple II games, both through his own company, and later, at Origin Systems. And while he has since gone on bigger and better things (did I mention that was one of the developers of Doom?), he is an avid collector of Apple II games, hardware and memorabilia.

For this week’s blog post I had planned to write about my experiences at E3, the Electronic Entertainment Expo, but then I received an invitation to attend an even more noteworthy event — a reunion at the home of Doom developer John Romero for many of us who had developed games for the Apple II computer. In addition to being a historic figure in game development himself, John has a deep love for the history of Apple II games. John’s first published game, Scout Search, appeared in the June 1984 issue of inCider, a popular Apple II magazine during the 1980s, and he went on to develop a number of Apple II games, both through his own company, and later, at Origin Systems. And while he has since gone on bigger and better things (did I mention that was one of the developers of Doom?), he is an avid collector of Apple II games, hardware and memorabilia.

My own introduction to the Apple II was through Gene Sprouse, one of my instructors at Cal State University, Northridge. I was enrolled in his COBOL business programming course, but when he found that I was using the university’s computer to print out pictures of the starship Enterprise, he asked me to stay after class. But instead of criticizing me for wasting valuable computer time, he offered me a job. Gene and several other partners owned Rainbow Computing, the second computer store to open in Los Angeles, and wanted me to work as a clerk in his store. Of course, I happily accepted.

Not long after I started working at Rainbow Computing, Gene and his main partner, Glenn Dollar, became registered dealers of a new computer called the Apple II. Prior to this time, computers were sold to hobbyists, because they had to be assembled and were difficult to use. However, the Apple II, created by engineer Steve Wozniak and his business partner, Steve Jobs, was designed for home use. It could be connected to the family’s home television set and came with game paddles.

However, there wasn’t much software (what the kids these days would call “apps”) available for it when it game out, not even games. But the machine did come with its own, easy-to-use, programming language, BASIC. So, what a lot of our customers would do after purchasing an Apple II was to program their own software. Then, they might make some copies of it (on standard audio cassette tape), photocopy some documentation, put everything into a ziplock bag, and then bring it to our store to sell. We eventually received such an inventory of games and other software to sell that we opened up a mail-order business, and filling those orders became my responsibility.

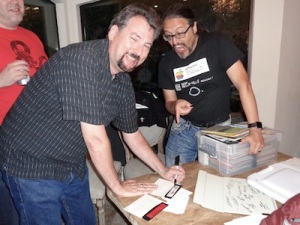

John asks me to sign his copies of The Prisoner and Prisoner 2. John asks me to sign his copies of The Prisoner and Prisoner 2. |

Some of our customers also decided to start their own game companies — Ken Williams of Sierra Online, Dave Gordon of Programma International, and Sherwin Steffin of Edu-Ware Services. Upon learning that I was studying computer science and had an interest in games, Sherwin asked me if I would write some games for his company. So, while I was finishing up my degree, I created Space II (a text-based RPG), Windfall (an oil crisis simulation), and Network (a television programming experience) for Edu-Ware, before joining the company full-time when I graduated. During my time at Edu-Ware, I programmed my most well-known Apple II games, the text-based adventure The Prisoner, and its hi-res graphics update, Prisoner 2.

Looking over the Apple II hardware partygoers brought to be signed, with Softape co-founder Gary Koffler Looking over the Apple II hardware partygoers brought to be signed, with Softape co-founder Gary Koffler |

Another major software publisher of this early era was Softape. Co-founded by William Smith, Bill Depew and Gary Koffler, The company published computer games, utilities and productivity programs for the Apple II family. Softape produced a newsletter magazine Softalk, but it was taken over by Margot Comstock and Al Tommervik in 1980 and re-designed into the Apple II enthusiast magazine Softalk. The startup capital for Softalk came money Margot had won on the television game show Password. Margot told host Allen Ludden that she wanted to use her winnings to buy a computer, and after several trips to various computer stores, she settled on the Apple II.

With Softalk founders Margot Comstock and Al Tommervick. With Softalk founders Margot Comstock and Al Tommervick. |

It is impossible to overstate the influence Softalk had in forging a community out of all these “mom-and-pop” companies started by devotees of the Apple II. Unlike other computer magazines that generally focused on a specific, narrow subject matter or market segment, Softalk gave broad coverage to all parts of the Apple world of the time, from programming tips to game playing, from business to home use, including computing as an industry, a hobby, a tool, a toy, and a culture.

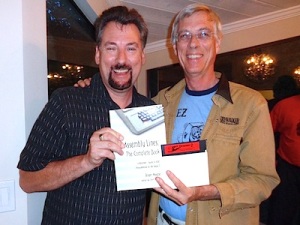

With Assembly Lines author, Scott Wagner. With Assembly Lines author, Scott Wagner. |

Another characteristic of the magazine was a playful, insider-like voice. The experts in those early days seemed to chat in their own relaxed language about the techniques and elements of their world. One of these experts was Roger Wagner, who wrote a column (and eventually a book) on programming in assembly language for the Apple II. I probably learned more about sophisticated programming from Roger than I did in college, allowing me to program graphics engines, natural language parsers, and maze generators for my games in the Apple’s 6502 assembly language.

Eventually, I went on to form my own game publishing company, Electric Transit in 1985. We specialized in real-time 3D simulations games for the Apple II (and the IBM PC). Because games were still being sold through thousands of individual mom-and-pop retailers throughout the country, and, so we needed a distributor to get our product to those retailers. We turned to another young company that had started just a couple of years before us, Electronic Arts, and we became their first affiliated label software publisher. Unfortunately, being the first, EA made a lot of initial mistakes with us, such as overestimating orders of our product, and within two years, we were out of business.

With Dick Tracy programmer, Steve Baker. With Dick Tracy programmer, Steve Baker. |

I then joined The Walt Disney Company in 1987 as its very first game producer. I produced a number of games for the Apple II (as well as other platforms) at Disney, and my last Apple II game was based on the film Dick Tracy. Programmed by Steve Baker, it was one of the most technically sophisticated Apple games I ever produced, thanks to Steve’s audio routines, but two months before it was complete, our marketing department determined that the market for Apple II games had died out and requested the project to be cancelled.

With our gracious host, John Romero. With our gracious host, John Romero. |

Flash forward 10 years: John Romero holds a party at his company Ion Storm for a reunion of Apple II game developers. When I received the invitation, nothing could stop me from hopping on a plane to Dallas. There I met some of the people that produced some of my favorite Apple II games, including Dan Gorlin of Choplifter fame.

Flash forward another 15 years, to last week. While I’m preparing for E3, I receive a Facebook message from Softape co-founder Gary Koffler that John was holding another reunion party at his home in the Santa Cruz area that weekend. It took surprisingly little effort to convince my wife, Char, to make the five-and-a-half hour drive up to attend the party (it helps that we decided to spend the night at a hotel along the beach.

Partygoers in the Casa Romero backyard. Partygoers in the Casa Romero backyard. |

We arrived a couple of hours late, and the party is in full force. John and his wife, Brenda, have a lovely home in the forested area. Too my delight, I see the house is decorated with items from John’s games and games in general. But best of all were the terrific people who showed up. In addition to the ones pictured above, here are some of the people I had the pleasure of seeing again (some, after a decade or two) or whom I have long admired but never had a chance to meet before.

2015 Apple ][ Reunion t-shirt. 2015 Apple ][ Reunion t-shirt. |

Af about 11pm, Char and I started to nod off, so we had to take our leave. John was nice enough to make t-shirts for us to remember the event. It was sad to go, but I hear that John is already planning another of these reunions, one with hopefully even more of us Apple II veterans in attendance.