Blog Archives

Where Do Game Designers Get Their Ideas From?

Although I wrote last week that there is no “idea guy” position in the game industry, game designers do frequently need to come up with ideas as part of their other responsibilities. After all, every game starts out as an idea. However, while many gamers believe that a game designer comes up with and then develops a game exactly as he or she originally envisioned it, game design is a much more complicated process. Some games come from one powerful idea, but most are formed by combining many ideas to create a unique whole. It’s very possible that initial ideas will be (or should be) abandoned, and lots of new ideas will be considered during the process.

Although I wrote last week that there is no “idea guy” position in the game industry, game designers do frequently need to come up with ideas as part of their other responsibilities. After all, every game starts out as an idea. However, while many gamers believe that a game designer comes up with and then develops a game exactly as he or she originally envisioned it, game design is a much more complicated process. Some games come from one powerful idea, but most are formed by combining many ideas to create a unique whole. It’s very possible that initial ideas will be (or should be) abandoned, and lots of new ideas will be considered during the process.

Novice game designers tend to mash together existing genres, mechanics, and themes. They envision new games as collages of existing game component, or put a slight twist on an existing game: “Street Fighter…. with politicians!”. As a result, they focus on the mechanics and theme rather than creating unique player experiences.

A more experienced game designers will shift their focus so that instead of having visions of a specific game, they will be interested in exploring broad or incomplete ideas. The ideas can be about theme, they can be about mechanics, they can be about player experiences… really, they can be about anything.

Now these ideas don’t come out of thin air. Game designers are influenced by personal interests and hobbies. For example, for the first game I made professional, Space II, I took concepts I learned about shamanism in an anthropology class, and turned it into a space colonization game in which the player’s goal was to acquire converts to a new religion. In my second game, Windfall: An Oil Crisis Simulation, I applied queuing theory and supply & demand economics to the 1979 oil crisis. For my third game, Network, I combined principles from a mass communication class with the movie Network and created a satirical network programming simulation.

When coming up with new concepts, I looked for my inspiration in everywhere but other games. This is why I recommend to my game design students that they spend a significant part of every day doing something other than playing games so that they have well-rounded experiences upon which to draw:

- Read a book

- See a play

- Listen to music

- Draw a landscape

- Go hiking

- Do volunteer work

- Take an online course in something that has nothing to do with making games.

Ideas can strike you at any time. I get my best ideas while driving; other might get theirs while taking a shower or having a dream. So, another thing I recommend to my students is that they keep a game design journal with them at all times for jotting down their ideas when they strike. The journal should be small and convenient enough that you can place it on their nightstand or take it with you everyone you go.

Ideas rarely come out as fully formed. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes the classic stages of creativity:

- Preparation: Becoming interested in a topic

- Incubation: Period where ideas “churn around” in your subconscious

- Insight: The “aha!” moment, where an idea comes together

- Evaluation: Deciding whether the insight is worth pursuing

- Elaboration: Fleshing out the idea

This is the typical birth process for an idea, but it’s possible to skip or jump around stages. Perhaps you’ll have an “aha!” moment without even realizing you were interested in the topic. Or maybe you’ll decide that an idea is worth pursuing, but instead of fleshing it out, you’ll spend more time letting it churn around in your head.

Fleshing out an idea is where a designer’s real work comes in, and in doing that work, they need to keep a healthy emotional distance. Obviously, they are excited by their ideas, but they know many ideas never work out, so it’s dangerous to become attached to an untested one. They also know that the initial conception is very rarely the best implementation, so keeping an open mind and keeping nothing sacred will tend to result in better final games.

Be advised that professional game designers don’t just work on their own ideas; often they are called upon to develop ideas that they are given to work on. So, besides coming up with their own brilliant inspirations, they may be called upon to flesh out concepts coming from sources such as these:

- Licensing Hook: Your business development manager has just acquired the licensing rights to make a game based upon the hit TV show The Hooker and the Priest, and now you must somehow turn that into a game.

- Technology Hook: Your engine programmer came up with a method of rendering rainbows that look so cool, you are tasked with creating a game based on rainbows.

- Filling A Gap: Your marketing director says that even though your company has made a very popular real-time strategy game and first-person shooter game, it also needs to make a platformer to cover the entire customer base, and you are charged with designing one.

- Following Coattails: Your vice president of sales reports that your competitors new werewolf survival game is selling through the rough, and now all of the retailers are clamoring for more werewolf survival games.

- Sequels: Your company has done very well with their Boswell Badger endless runner game franchise, but the game’s leader designer is burned out on badgers, and you’ve been called in to design Boswell Badger VIII.

- Orders From Above: Your studio manager had a dream about spiral staircases last night, and was so exited about the idea, he orders you to build a game about spiral staircases.

Professional game designers are probably more often called upon to develop game ideas that came from someone else than they are to work on their own. Admittedly, it can be difficult to get enthusiastic about someone else’s idea, but that’s what you need to do if you’re a professional. However, sometimes it’s necessary — desirable even — to call in for help, and so next week, I will write about how to brainstorm ideas with other team members.

Trying My Digits At Teaching Analog Game Design

I grew up playing popular board games with my family — Candyland, Chutes and Ladders, Operation, Life, Clue, Monopoly, Scrabble, Risk, Stratego. Eventually, I began to design my own boardgames for fun. In my college years, I discovered Dungeons & Dragons, and that role-playing game helped me form my early ideas about game design as I began to develop video games. Three decades later, when I was working at the Spinmaster toy company, I renewed my interest in board games by participating in the company’s weekly board game playtesting sessions.

I grew up playing popular board games with my family — Candyland, Chutes and Ladders, Operation, Life, Clue, Monopoly, Scrabble, Risk, Stratego. Eventually, I began to design my own boardgames for fun. In my college years, I discovered Dungeons & Dragons, and that role-playing game helped me form my early ideas about game design as I began to develop video games. Three decades later, when I was working at the Spinmaster toy company, I renewed my interest in board games by participating in the company’s weekly board game playtesting sessions.

One of the classes in our game program at The Los Angeles Film School is Analog Game Theory, which introduces students to game design principles for board and card games that do not require technology to create engaging experiences. Our AGT instructor moved out of state recently, and while we were waiting for to bring aboard a replacement instructor, I was given the opportunity to teach the class, and what a fun time it was for me!

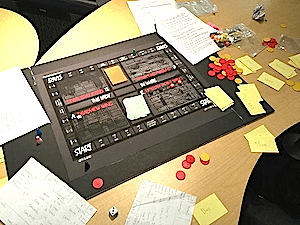

During each of the first three class sessions, I had the students play and then analyze a board game — Carcasonne, Puerto Rico, and Settlers of Catan, respectively. After discussing the considerations that the game designers made in creating each of the games, I had the students do a quick game jam, making a game games based upon a particular play value, a game mechanic, or use of randomness for a game element other than player movement. Then, for the last seven sessions of the class, I divided the students into three teams to develop a final project for our bi-monthly Analog Game Fair.

It was the physical aspects of the games that most concerned me, having only worked professionally in digital games, but I was very pleasantly surprised with the polish that some of the students brought to their games.

Lady In White was a horror-themed game created by a three-person team. Players would roll dice to move spaces around the game board to collect resources needed build graves and other graveyard structures used to collect souls with the goal of collecting a certain number of souls to win the game. The player could collect the more common resources, Dirt and Wood, by passing them as they moved around the board. However, the more rare resources could only be obtained by landing on a specific space or by purchasing them using the game’s currency, gold. Gold was collected by landing on marked spaces or by drawing a card with a random effect. These cards could also have negative effects on the player such as losing all of the resources they had collected so far.

Lady In White was a horror-themed game created by a three-person team. Players would roll dice to move spaces around the game board to collect resources needed build graves and other graveyard structures used to collect souls with the goal of collecting a certain number of souls to win the game. The player could collect the more common resources, Dirt and Wood, by passing them as they moved around the board. However, the more rare resources could only be obtained by landing on a specific space or by purchasing them using the game’s currency, gold. Gold was collected by landing on marked spaces or by drawing a card with a random effect. These cards could also have negative effects on the player such as losing all of the resources they had collected so far.

The game board fit into the game’s theme well, but there was a problem with the game resources. First, the difficulty of acquiring the resources for the various graveyard structures did not correspond to the amount of souls each structure could capture. After doing some quick analysis of the cost of various structures in terms of gold, it was obvious there was only one structure worth of purchasing. Also, the game had too many resources with too little differentiation between them, so the game was basically about collecting resources as quick as you can to generate enough souls to win the game. Finally, when four players played the game, it took too long to generate enough souls to win, and we wound up quitting the game after an hour, as there was too little variety to keep us occupied. Many of these flaws should have been found in the three playtest sessions we had before Game Fair, but it appears that the players who were playtesting the game were not critical enough.

Outfall was a board game inspired by the computer role-playing game Fall Out. Players start the game by choosing which character class to play, which determine which of four stats would be used for determining success with other characters. Throughout the game players would draw equipment cards that would be used to modify their states. When players landed on board location representing an enemy character or one occupied by another player, they would do battle by rolling dice and referring to their stats to determine which one the battle, usually with some positive benefit to the winner and a negative penalty to the loser, with the effects varying based on their character class. Equipment cards are drawn by players to reveal a potential item that they could use towards a players stats. Other elements that added uncertainty to the game were additional cards that the players could collect and play at various points in the game to add benefits to themselves or penalize others.

Outfall was a board game inspired by the computer role-playing game Fall Out. Players start the game by choosing which character class to play, which determine which of four stats would be used for determining success with other characters. Throughout the game players would draw equipment cards that would be used to modify their states. When players landed on board location representing an enemy character or one occupied by another player, they would do battle by rolling dice and referring to their stats to determine which one the battle, usually with some positive benefit to the winner and a negative penalty to the loser, with the effects varying based on their character class. Equipment cards are drawn by players to reveal a potential item that they could use towards a players stats. Other elements that added uncertainty to the game were additional cards that the players could collect and play at various points in the game to add benefits to themselves or penalize others.

This game was made by a four-person student team, but the team was hampered by two of its members being frequently absent during production. As a result, the game components lacked the polish of the other two games made in the class. The gameplay was fairly simple, yet it was engaging. Overall, it was a fun premise that could have been made richer given more time (and more involvement from the rest of the team.

The final game presented at our Game Fair was Galaxy Station, made by another three-student team. In this game, players traveled around a game board collecting materials necessary to enhance their spacecraft, which each enhancement bestowing certain benefits. The final version of the game featured gorgeous-looking components, but what really captivated me was a game mechanics that rotated the central path on the board with each phase of the game, opening up different paths and opportunities for players to collect rate resources from the circular side paths. The game was eye-catching from a visual stand-point and its gameplay was compelling as well.

The final game presented at our Game Fair was Galaxy Station, made by another three-student team. In this game, players traveled around a game board collecting materials necessary to enhance their spacecraft, which each enhancement bestowing certain benefits. The final version of the game featured gorgeous-looking components, but what really captivated me was a game mechanics that rotated the central path on the board with each phase of the game, opening up different paths and opportunities for players to collect rate resources from the circular side paths. The game was eye-catching from a visual stand-point and its gameplay was compelling as well.

All in all, my experience in teaching a class about creating board games turned out to be an even more fun experience than I anticipated, and it made me want to start playing board games again, although perhaps checking out some more recent games that are a bit more innovative than the ones from my youth.