Blog Archives

Remembering Wes Craven: Principled Man of Fear

I love horror. Not real-life horror like disease and poverty, but fantasy-horror. My favorite holiday is Halloween, my favorite Disneyland attraction is The Haunted Mansion, and when I was a kid, I made my own haunted house ride, charging neighborhood kids twenty-five cents to pull them on a wagon past scary scenes I set up in my garage. But mostly, I loved watching watching Universal horror movies (my favorite was the Wolfman).

I love horror. Not real-life horror like disease and poverty, but fantasy-horror. My favorite holiday is Halloween, my favorite Disneyland attraction is The Haunted Mansion, and when I was a kid, I made my own haunted house ride, charging neighborhood kids twenty-five cents to pull them on a wagon past scary scenes I set up in my garage. But mostly, I loved watching watching Universal horror movies (my favorite was the Wolfman).

As I grew up, my tastes in horror became more sophisticated. When I went to the movies with my friends, we watched Friday the Thirteenth, Halloween, and all the other slasher films aimed at the teenage audience. But my favorite horror film of all was A Nightmare on Elmstreet, directed by Wes Craven, who passed away yesterday at the age of 76 after a losing battle with brain cancer.

A Nightmare on Elm Street contains many biographical elements, taking inspiration from director Wes Craven’s childhood. The basis of the film was inspired by several newspaper articles printed in the Los Angeles Times in the 1970s on a group of Khmer refugees, who, after fleeing to the United States from the results of American bombing in Cambodia, were suffering disturbing nightmares, after which they refused to sleep. Some of the men died in their sleep soon after. Medical authorities called the phenomenon Asian Death Syndrome.

The film’s villain, Freddy Krueger, draws heavily from Craven’s early life. One night, a young Craven saw an elderly man walking on the sidepath outside the window of his home. The man stopped to glance at a startled Craven, and then walked off. This served as the inspiration for Krueger. Initially, Fred Krueger was intended to be a child molester, but Craven eventually decided to characterize him as a child murderer to avoid being accused of exploiting a spate of highly publicized child molestation cases that occurred in California around the time of production of the film.

By Craven’s account, his own adolescent experiences led to the naming of Freddy Krueger. He had been bullied at school by a child named Fred Krueger, and named his villain accordingly. Craven strove to make Krueger different from other horror-film villains of the era. “A lot of the killers were wearing masks: Leatherface, Michael Myers, Jason,” he recalled in 2014. “I wanted my villain to have a ‘mask,’ but be able to talk and taunt and threaten. So I thought of him being burned and scarred.” He also felt the killer should use something other than a knife, which was too common. “So I thought, How about a glove with steak knives?”

What I most enjoyed about the film was that it was in some ways a thinking person’s horror film. By having the villain, Freddy Krueger, invade his victims’ dreams, the film toyed with the audience’s perception by blurring the boundary between the real and the imaginary. The film itself preys on archetypal fears and imagery: the myth of the bogeyman, the vulnerability of a sleeping victim, and the power of the unconscious conjuring up the worst horrors imaginable.

A Nightmare On Elm Street is considered by many, including me, to be one of the best films of 1984, so imagine my delight when, twelve years later, I was meeting with film’s director about making a new horror project, but in my own creative medium, video games.

I was the Creative Director of a small game publisher called Cyberdreams, which specialized in working with famous names from the fields of science fiction, fantasy and horror in adapting their works to video games. Previously, I had worked with writer Harlan Ellison in creating a game version of his classic short story I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream as well as artist H.R. Giger on using his macabre art as the inspiration for a game called Dark Seed. And now I was meeting with a master of film horror, Wes Craven.

Craven had approached us with a concept called Principles of Fear, which was about exploring the various causes of fear. The goal was to create an action-adventure game which encompasses all levels of human fear and conflict within a challenging game scenario. Although many games did justice in rendering ferocious combat, and others take great care in presenting a psychological challenge, few successfully combine both elements.

Craven had approached us with a concept called Principles of Fear, which was about exploring the various causes of fear. The goal was to create an action-adventure game which encompasses all levels of human fear and conflict within a challenging game scenario. Although many games did justice in rendering ferocious combat, and others take great care in presenting a psychological challenge, few successfully combine both elements.

As Craven described his ideas across several meetings, I found him to be an extremely intelligent, erudite and charming man. He was also a master storyteller, in person as well as on-screen. I knew right away that working with him would be delight.

I contracted game developer Asylum Entertainment, whose credits included the military strategy adventure Allied General for SSI and SimFarm for Maxis, to develop the CD-ROM action-adventure. I also found working with Asylum and its president, Brett Durett, to be yet another delightful experience, as we worker together to turn Wes Craven’s insights on the essence of fear into a compelling three-dimensional game taking place in what was essentially a haunted house.

We had thought we had succeeded when we demonstrated an early prototype of the game at the 1997 Electronic Entertainment Expo when About Games awarded our game a Bronze Medal award for Best of E3 — Interactive Fiction.

Unfortunately, Wes became deeply involved in developing a new movie at this time, and we only had access to his manager, who apparently had little understanding of games or the process of making them. When I demonstrated our award-winning E3 demo to her, it did not meet whatever expectations she had about what the video game would be like. She insisted on canceling the project and we could not talk her out of it.

And so I woke up from our dream of working with Wes Craven with nothing to show for it but some good memories of our meetings with him. Now with his passing, I’ll never again have a chance to apply his Principles of Fear. Lost opportunities are one horror that I do not enjoy at all.

Memories of H.R. Giger

Yesterday Swiss surrealist, sculpture and set designer H. R. Giger who mined his own nightmares in creating phantasmagorical works of art passed away in a hospital near his home in Zürich, Switzerland after having suffered injuries in a fall. He was 74 years old.

Yesterday Swiss surrealist, sculpture and set designer H. R. Giger who mined his own nightmares in creating phantasmagorical works of art passed away in a hospital near his home in Zürich, Switzerland after having suffered injuries in a fall. He was 74 years old.

I first became acquainted with Giger’s work through the cover art he created for the Emerson, Lake and Palmer album Brain Salad Surgery my brother had given me for Christmas. Like most of Giger’s creations, the cover was a highly idiosyncratic blend machines and biology that greatly appealed to me as a teenager who was a fan of science fiction, horror, and fantasy.

Years later, I encountered Giger’s work again in the 1979 film Alien. He was part of the creative team that won an Academy Award for visual effects the that landmark science fiction / horror film, having personally designed the alien creature through all stages of its life, from egg to face- hugger, to chest-burster, to eight-foot-tall monster. That movie, along with its sequel Aliens, remain two of my favorite films, in no small part due to Giger’s contributions.

You can therefore imagine how thrilled I was when I had an opportunity to meet Giger at his Zürich, home in 1995. I was working as a producer at video game publisher Cyberdreams, which developed games in collaboration with famous personalities in the fields of science fiction, fantasy and horror. Prior to me joining the company, Cyberdreams had published a point-and-click adventure game called Dark Seed about a writer named Mike Dawson, who had recently bought a mysterious old mansion. On his first night at the house, Mike has a nightmare about being imprisoned by a machine that shoots an alien embryo into his brain. He wakes up with a severe headache and, after taking some aspirins and a shower, explores the mansion. He finds clues about the previous owner’s death, which reveal the existence of a parallel universe called the Dark World ruled by sinister aliens called the Ancients. This Dark World is based on Giger’s art.

The game was a big enough success that I was assigned the task of producing a sequel. I hired game designer and novelist Raymond Benson to design the game, artist Jeff Hilbers to do the artwork for the “Normal World”, and developer Destiny Software Productions to do the programming and “Dark World” artwork. As with the first version of the game, all of the “Dark World” art was based upon Giger’s existing art collection.

Six months into the project we had completed enough to visit Giger and get his feedback on our progress. Three of us traveled to Zürich: Cyberdreams Art Director Peter Delgado, an artist from Destiny Software Productions, and myself. After a very long plane flight and an overnight stay at our hotel, we hopped into a taxi and rode to Giger’s home, an unassuming two-story house in a middle-class residential neighborhood. The time was a little after 5p.m., but it was winter, so the entire street was dark except for a single light shining down upon Giger’s walkway. Standing in the middle of the light cone was Giger himself, clad entirely in black. The scene reminded me of the poster from The Exorcist.

Six months into the project we had completed enough to visit Giger and get his feedback on our progress. Three of us traveled to Zürich: Cyberdreams Art Director Peter Delgado, an artist from Destiny Software Productions, and myself. After a very long plane flight and an overnight stay at our hotel, we hopped into a taxi and rode to Giger’s home, an unassuming two-story house in a middle-class residential neighborhood. The time was a little after 5p.m., but it was winter, so the entire street was dark except for a single light shining down upon Giger’s walkway. Standing in the middle of the light cone was Giger himself, clad entirely in black. The scene reminded me of the poster from The Exorcist.

Giger led us into his home, which was also clad entirely in black — floors, walls and ceilings. Most of the furnishing were modest, save for a biomechanical table and hairs in his living room that he had originally designed for three Giger Bars (the original was in Tokyo, and two more were built in his native Switzerland). Scattered throughout the house were samples of his artwork and sculptures. As we stared in awe at everything, Giger suddenly realized he had nothing to offer his guests, and so he jogged off to the corner market to get some tea and cookies.

When he returned, we sat down in his living room and attempted to make small talk (Giger’s command of English was minimal, but he tried hard). As he stroked the cat sitting in his lap, the cat farted. “Milky! You stink! You stink!”, Giger exclaimed, tossing the cat onto the floor. We thought then would be a good time to end the casual conversation and take a look at the game prototype we had brought with us.

After spending several minutes looking at our point-and-click adventure, Giger told us that he had a completely different idea for the game. He wanted to know if we could turn it into a game where the player climbed up a series of catwalks inside a pyramid, and when he got to the top, he would find himself in another pyramid, with the game being a succession of pyramids. Using my best diplomatic demeanor, I told him that that was very creative idea, but since this was a sequel to the previous game, fans would expect it to be an adventure game like the first one was.

This did not please Giger at all. “Mia, Mia”, he muttered to himself, referring to the name of his ex-wife, who was now acting as his agent. After a few moments, he wandered off to another part of the house, leaving us alone in the living room. After about fifteen minutes, I asked my art director, Peter, to look for him (Peter had met Giger on a previous visit, and the two seemed to get along well). When Peter returned, he said that he found Giger sitting in his badroom, apparently talking to his deceased girlfriend Li, who had committed suicide twenty years ago. We decided it would be a good time to leave.

The next evening we returned to Giger’s home, Giger’s manager Mia was there to greet us. She spoke English better than her ex-husband did, and after a round of introductions, she pressed on the issue of changing the game, I said that it was too late to move into a new direction. Giger and Mia then began speaking to each other in Swiss very energetically. I had taken two years of German in high school, and so I tried to follow what they were saying, but the only thing I understood is when they stopped their conversation to look at me, and Mia said, “Er spricht Schweiz Deutsch!” (“He speaks Swiss German!”).

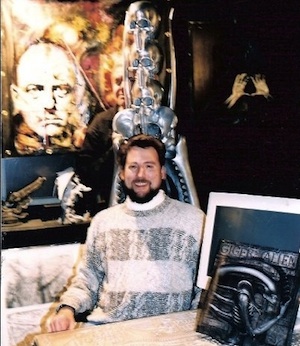

“However”, I interrupted. “Here’s what we can do. We can have the character walk all around the world on catwalks, just like in Giger’s idea. But we want to show off all of Giger’s wonderful artwork, so let’s leave the buildings in.” That concession seemed to please them, and the mood changed for the better. Giger relaxed and said that he was happy, and then suggested each of us take a picture sitting in one of the chairs from his Giger bar.

“However”, I interrupted. “Here’s what we can do. We can have the character walk all around the world on catwalks, just like in Giger’s idea. But we want to show off all of Giger’s wonderful artwork, so let’s leave the buildings in.” That concession seemed to please them, and the mood changed for the better. Giger relaxed and said that he was happy, and then suggested each of us take a picture sitting in one of the chairs from his Giger bar.

And that was the last opportunity I had to see Giger. The entire experience was truly surreal, and I’m very happy to have this photo as a momento of the experience and proof that it was not all a dream — or a nightmare!