Category Archives: My Career

My First Video Game

The first game I ever made professionally was a sequel to a text-based role-playing game for the Apple II personal computer called Space, which in turn was inspired by a science fiction pen-and-paper RPG called Traveller. The year was 1979, and I was working as a clerk at Rainbow Computing, a small computer store owned by a couple of my professors at California State University, Northridge, where I was a Computer Science major. One of our regular customers, Sherwin Steffin, had recently been laid off from UCLA’s Educational Media department, and he had decided to start his own company, Edu-Ware, to publish educational software.

The first game I ever made professionally was a sequel to a text-based role-playing game for the Apple II personal computer called Space, which in turn was inspired by a science fiction pen-and-paper RPG called Traveller. The year was 1979, and I was working as a clerk at Rainbow Computing, a small computer store owned by a couple of my professors at California State University, Northridge, where I was a Computer Science major. One of our regular customers, Sherwin Steffin, had recently been laid off from UCLA’s Educational Media department, and he had decided to start his own company, Edu-Ware, to publish educational software.

However, he and his partner, a UCLA student named Steve Pederson, also published some games. The two used their Space RPG to convince Rainbow Computing to provide Pederson with an Apple II computer in exchange for receiving product at cost. When Pederson and Steffin learned that Rainbow had announced Space in its mail order catalog before the game was completed, the two spent twenty-four straight hours debugging the game without the benefit of Edu-Ware even owning a printer at the time.

When the game turned out to be successful, Steffin asked me if I’d be interested in designing and programming a sequel to it. Of course, I jumped at the chance. I had played a bit of Dungeons & Dragons, both the official version and a simplified version created by some of my college friends, and that had informed much of my initial knowledge about game design.

As for the programming, personal computer games of that era were either programmed the version of BASIC (Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) that came with the computer, or assembly language, which the computer’s operating system was written in. I had learned both BASIC and assembly language programming in my college courses, so I already had the knowledge I needed to program the game.

My early ambitions in the game industry was to create games that offered more than entertainment value. I wanted to also either teach players something new or provide them with different insights, just as my favorite novels did. So, for this sequel, I created two additional scenarios for the player’s Space characters.

- Shaman: Characters launch their career as a religious practitioner who is tasked with building a cult on a new world, using an all-terrain vehicle to travel across the planet and accumulate followers. I based this scenario on material from an anthropology class I had taken.

- Psychodelia: Characters experiment with mind-altering drugs, which may boost or retard various traits, which is the only way they can be altered once a character leaves military service. This was my commentary about the risk of taking drugs, which some of my acquaintances experimented with.

Actually, I saw my entire design as an exercise in risk-benefit analysis, as the player’s character is presented with dangerous options throughout the game, and the player must determine whether the potential rewards are worth the possible risks.

I programmed both scenarios in a two week period, in between my college studies. I don’t recall how well the game sold, but I recall receiving about two hundred dollars in royalty payments, which seemed at the time like a fortune.

Both games in the series were well-reviewed in the gaming press, with my sequel receiving an A- rating from Peelings magazine, and the games were notable for not only being one of the first science fiction RPG’s to appear on personal computers, but also for providing a level of realism not found in other games of the time.

Unfortunately, the Space saga was not without its upheavals. Did I say earlier that the original Space was inspired by Traveller? Well, the truth was, the game used the exact same mechanics for character generation that Traveller did. In fact, the games were so close that Traveller‘s publisher, Game Designers Workshop, sued Edu-Ware for copyright infringement. The case was eventually settled out of court, with Edu-Ware agreeing to stop selling the two games.

By that time, I had graduated college and was a full-time employee for Edu-Ware. One of my first tasks was to write an all-new science fiction role-playing game, but this time in graphics instead of text. I reworked some of the scenarios from the original Space games, but created my own character generation system as well as a graphics engine.

This new RPG series was called Empire, and the first in the trilogy of games, World Builders, which took me three months to design and program, won Electronic Games magazine’s award for Best Science Fiction/Fantasy Game of 1983.

Trying My Digits At Teaching Analog Game Design

I grew up playing popular board games with my family — Candyland, Chutes and Ladders, Operation, Life, Clue, Monopoly, Scrabble, Risk, Stratego. Eventually, I began to design my own boardgames for fun. In my college years, I discovered Dungeons & Dragons, and that role-playing game helped me form my early ideas about game design as I began to develop video games. Three decades later, when I was working at the Spinmaster toy company, I renewed my interest in board games by participating in the company’s weekly board game playtesting sessions.

I grew up playing popular board games with my family — Candyland, Chutes and Ladders, Operation, Life, Clue, Monopoly, Scrabble, Risk, Stratego. Eventually, I began to design my own boardgames for fun. In my college years, I discovered Dungeons & Dragons, and that role-playing game helped me form my early ideas about game design as I began to develop video games. Three decades later, when I was working at the Spinmaster toy company, I renewed my interest in board games by participating in the company’s weekly board game playtesting sessions.

One of the classes in our game program at The Los Angeles Film School is Analog Game Theory, which introduces students to game design principles for board and card games that do not require technology to create engaging experiences. Our AGT instructor moved out of state recently, and while we were waiting for to bring aboard a replacement instructor, I was given the opportunity to teach the class, and what a fun time it was for me!

During each of the first three class sessions, I had the students play and then analyze a board game — Carcasonne, Puerto Rico, and Settlers of Catan, respectively. After discussing the considerations that the game designers made in creating each of the games, I had the students do a quick game jam, making a game games based upon a particular play value, a game mechanic, or use of randomness for a game element other than player movement. Then, for the last seven sessions of the class, I divided the students into three teams to develop a final project for our bi-monthly Analog Game Fair.

It was the physical aspects of the games that most concerned me, having only worked professionally in digital games, but I was very pleasantly surprised with the polish that some of the students brought to their games.

Lady In White was a horror-themed game created by a three-person team. Players would roll dice to move spaces around the game board to collect resources needed build graves and other graveyard structures used to collect souls with the goal of collecting a certain number of souls to win the game. The player could collect the more common resources, Dirt and Wood, by passing them as they moved around the board. However, the more rare resources could only be obtained by landing on a specific space or by purchasing them using the game’s currency, gold. Gold was collected by landing on marked spaces or by drawing a card with a random effect. These cards could also have negative effects on the player such as losing all of the resources they had collected so far.

Lady In White was a horror-themed game created by a three-person team. Players would roll dice to move spaces around the game board to collect resources needed build graves and other graveyard structures used to collect souls with the goal of collecting a certain number of souls to win the game. The player could collect the more common resources, Dirt and Wood, by passing them as they moved around the board. However, the more rare resources could only be obtained by landing on a specific space or by purchasing them using the game’s currency, gold. Gold was collected by landing on marked spaces or by drawing a card with a random effect. These cards could also have negative effects on the player such as losing all of the resources they had collected so far.

The game board fit into the game’s theme well, but there was a problem with the game resources. First, the difficulty of acquiring the resources for the various graveyard structures did not correspond to the amount of souls each structure could capture. After doing some quick analysis of the cost of various structures in terms of gold, it was obvious there was only one structure worth of purchasing. Also, the game had too many resources with too little differentiation between them, so the game was basically about collecting resources as quick as you can to generate enough souls to win the game. Finally, when four players played the game, it took too long to generate enough souls to win, and we wound up quitting the game after an hour, as there was too little variety to keep us occupied. Many of these flaws should have been found in the three playtest sessions we had before Game Fair, but it appears that the players who were playtesting the game were not critical enough.

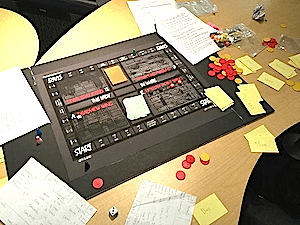

Outfall was a board game inspired by the computer role-playing game Fall Out. Players start the game by choosing which character class to play, which determine which of four stats would be used for determining success with other characters. Throughout the game players would draw equipment cards that would be used to modify their states. When players landed on board location representing an enemy character or one occupied by another player, they would do battle by rolling dice and referring to their stats to determine which one the battle, usually with some positive benefit to the winner and a negative penalty to the loser, with the effects varying based on their character class. Equipment cards are drawn by players to reveal a potential item that they could use towards a players stats. Other elements that added uncertainty to the game were additional cards that the players could collect and play at various points in the game to add benefits to themselves or penalize others.

Outfall was a board game inspired by the computer role-playing game Fall Out. Players start the game by choosing which character class to play, which determine which of four stats would be used for determining success with other characters. Throughout the game players would draw equipment cards that would be used to modify their states. When players landed on board location representing an enemy character or one occupied by another player, they would do battle by rolling dice and referring to their stats to determine which one the battle, usually with some positive benefit to the winner and a negative penalty to the loser, with the effects varying based on their character class. Equipment cards are drawn by players to reveal a potential item that they could use towards a players stats. Other elements that added uncertainty to the game were additional cards that the players could collect and play at various points in the game to add benefits to themselves or penalize others.

This game was made by a four-person student team, but the team was hampered by two of its members being frequently absent during production. As a result, the game components lacked the polish of the other two games made in the class. The gameplay was fairly simple, yet it was engaging. Overall, it was a fun premise that could have been made richer given more time (and more involvement from the rest of the team.

The final game presented at our Game Fair was Galaxy Station, made by another three-student team. In this game, players traveled around a game board collecting materials necessary to enhance their spacecraft, which each enhancement bestowing certain benefits. The final version of the game featured gorgeous-looking components, but what really captivated me was a game mechanics that rotated the central path on the board with each phase of the game, opening up different paths and opportunities for players to collect rate resources from the circular side paths. The game was eye-catching from a visual stand-point and its gameplay was compelling as well.

The final game presented at our Game Fair was Galaxy Station, made by another three-student team. In this game, players traveled around a game board collecting materials necessary to enhance their spacecraft, which each enhancement bestowing certain benefits. The final version of the game featured gorgeous-looking components, but what really captivated me was a game mechanics that rotated the central path on the board with each phase of the game, opening up different paths and opportunities for players to collect rate resources from the circular side paths. The game was eye-catching from a visual stand-point and its gameplay was compelling as well.

All in all, my experience in teaching a class about creating board games turned out to be an even more fun experience than I anticipated, and it made me want to start playing board games again, although perhaps checking out some more recent games that are a bit more innovative than the ones from my youth.