Category Archives: Games and Society

#GDC2015 Post-Mortem

I’ve gone to about a dozen of annual Game Developers Conferences since the second one in 1988. I would attend every year except that either I’m too busy to take several days off of work, or I just can’t afford the $1500 price tag (early bird rate) for a full conference pass that year. Unless the company that I’m currently working for offers to pay me to attend so that I can get some business done at the conference, I will either submit a speaking proposal so that, if accepted, I can get in free as a speaker, or simply pay for just the far-less expensive Expo Pass. This year I good the former route.

I’ve gone to about a dozen of annual Game Developers Conferences since the second one in 1988. I would attend every year except that either I’m too busy to take several days off of work, or I just can’t afford the $1500 price tag (early bird rate) for a full conference pass that year. Unless the company that I’m currently working for offers to pay me to attend so that I can get some business done at the conference, I will either submit a speaking proposal so that, if accepted, I can get in free as a speaker, or simply pay for just the far-less expensive Expo Pass. This year I good the former route.

Last summer the topic of ageism in the game industry fell upon my shoulders when I wrote a Facebook post about how a game studio declined to even interview me for a position on the same day that Empire Magazine named Vampire: The Masquerade — Bloodlines one of the 100 greatest games ever made. When people suggest that the reason was due to my age, I decided to write a Gamasutra article about ageism in the game industry, which in turn led me to be interviewed by the Voice of America about the topic.

So, when GDC issued a call for session submissions in September, I decided to propose a session in which a panel of experts would talk about the topic. I was very lucky to pull together a Dream Team consisting of former multimedia studio head turned designer/developer of games for seniors Laura Buddine, former Electronic Arts human resources manager turned consultant Jill Miller, former game designer turned university professor Mike Sellers, former Activision Vice President of Technology turned entrepreneur William Volk, and former executive recruiter turned career strategist Mary-Margaret Walker. I was even more fortunate that GDC accepted my proposal. However, they suggested that we do a series of micro-talks instead of a question & answer panel, and so we spent the next couple of months putting together and polishing a PowerPoint presentation, with assistance from a member of GDC’s Diversity Committee.

So, when GDC issued a call for session submissions in September, I decided to propose a session in which a panel of experts would talk about the topic. I was very lucky to pull together a Dream Team consisting of former multimedia studio head turned designer/developer of games for seniors Laura Buddine, former Electronic Arts human resources manager turned consultant Jill Miller, former game designer turned university professor Mike Sellers, former Activision Vice President of Technology turned entrepreneur William Volk, and former executive recruiter turned career strategist Mary-Margaret Walker. I was even more fortunate that GDC accepted my proposal. However, they suggested that we do a series of micro-talks instead of a question & answer panel, and so we spent the next couple of months putting together and polishing a PowerPoint presentation, with assistance from a member of GDC’s Diversity Committee.

Our session was picked to be highlighted on the Wednesday morning “Flash Forward” event. (Although the Conference lasts for five days, the first two days are devoted to special-topic “summits”, while the Conference proper lasts from Wednesday to Friday). SinceI had only planned to take Thursday and Friday off from teaching to attend the Conference, my fellow panelist Bill Volk agreed to present our session at the Flash Forward event. The only problem was that we had to present a single slide to show during our 45-second presentation, and due to technical glitches, miscommunications, and a very hectic day that Bill and I were having at our respective jobs, we wound up both putting together and submitting a slide. Fortunately, the folks running the event picked Bill’s much better version of the slide and the preview of our talk went very well.

With me mostly being on a teacher’s salary these days, I decided to attend the conference as inexpensively as I could. I decided to leave my home from Los Angeles at 4:30am on Thursday morning and do a 6-hour drive up to San Francisco. Good thing that I like driving! Through the GDC website, I had been able to book a very nice room at a Holiday Inn only five blocks from the Moscone Center at a very reasonable rate of $145/night. After checking into my hotel, I made the 15-minute walk to Moscone Center and picked up my Speaker’s badge and materials before noon.

According to news reports published afterwards, this was the biggest Game Developers Conference ever, with 26,000 attendees. However, for some reason it seemed to me to be more sparsely attended than recent previous conferences. I’m not sure why it seemed that way — perhaps because I didn’t arrive until it was half-way over. Still, I was able to run into someone I knew every five minutes or so — one of the benefits of being an old-timer in the industry. I ran into Heroes of Might & Magic music composer Rob King outside of South Hall, Doom co-creator John Romero in the Expo, IGDA founder Ernest Adams (big hat and all) in line to get into a session, and too many other colleagues and Facebook friends to namedrop here.

Meeting old friends and making new ones are, to me, the main benefits of attending a conference like this one. However, one networking secret I tell my students is that the best place to meet important people are in the lobbies and bars of the hotels surrounding the conference. I didn’t have a chance to take my own advice on this trip, as my time at the conference was short, and I had my speaker duties to attend to. One of these was meeting up with my fellow panelists (most of whom I had not seen in person in years — in fact, I had only met Laura Buddine once, twenty-five years ago) at a daily speaker’s lunch on the Thursday afternoon I arrived. Then, that evening I went to the Speaker’s Party (my other networking tip to my students — go to the many parties surrounding these events), where in between the free burritos, guacamole and beer (speaking has its privileges), I had an opportunity to meet Jesse Schell for the first time (regrettably, I was more impressed in meeting him than he was with me, and so our discussion didn’t last longer than a sentence or two).

As for the sessions — the problem for me at this stage in my career is that I could present most of the sessions I’m interested in attending, but there are always those few gems in which I learn a lot, and I can never tell ahead of time which will be which. Many of the sessions were about the emergence of Virtual Reality (an interest of mine, but unfortunately, I wasn’t able to attend any of these sessions), Indie development (I did attend a few of these to gleam some fresh advice to give my students), and diversity (the track covered by my own talk about ageism). My favorite session was a heavily-attended one that concluded Thursday’s events, #1ReasonToBe, a panel of female game industry personalities led by Brenda Romero discussing essentially the events surrounding #GamerGate. I never had the pleasure to listen to game journalist Leigh Alexander (announced a new project named Offworld specifically to focus on women and minorities and promote their efforts) speak in person before, and while she and the other panelists were quite poignant in discussing the attacks against female game developers, the most moving moment for me was when Brenda Romero placed an empty chair in front of the audience and then showed written of women who harassed or silenced by recent events.

I had the opportunity to advocate for my own “minority group”, game developers over the age of 50, the next morning. Our talk went extremely well, and you can read Gamasutra’s coverage of it here. Afterwards our panel met in the Wrap Up room to give advice to any developers who thought their careers had run into problems having to do with ageism. As our final discussions ended and our panel went their separate ways, I went over to the International Game Developers booth and talked to the IGDA leadership about starting a Special Interest Group for older developers. The IGDA leadership was very encouraging and supportive, so look for news about that in the near future.

I had the opportunity to advocate for my own “minority group”, game developers over the age of 50, the next morning. Our talk went extremely well, and you can read Gamasutra’s coverage of it here. Afterwards our panel met in the Wrap Up room to give advice to any developers who thought their careers had run into problems having to do with ageism. As our final discussions ended and our panel went their separate ways, I went over to the International Game Developers booth and talked to the IGDA leadership about starting a Special Interest Group for older developers. The IGDA leadership was very encouraging and supportive, so look for news about that in the near future.

After a final Speaker’s lunch, a couple of sessions, and a few more random run-ins with colleagues, I got into my car that evening and made the 6-hour drive back home. In some ways it didn’t feel like a very eventful GDC, but I suspect that some very good things will come out of it, particularly for members of the game development community who feel that they’ve been under-represented in the past.

What Was The First Video Game Company?

Every month the Los Angeles Film School runs an Open House for potential students. Although all of our in instructors have accomplished backgrounds, I am the one who gives the presentation on our Game Production Program, because, well, I’ve been lucky enough to have the most colorful career, and we think it’s interesting for folks to hear about the company’s I’ve worked at and games I made. So, I begin my presentation with, “I teach classes on game design, game development, game publishing, the impact of games on society, as well as the history of games. Let my tell you a little about my own history…”

Every month the Los Angeles Film School runs an Open House for potential students. Although all of our in instructors have accomplished backgrounds, I am the one who gives the presentation on our Game Production Program, because, well, I’ve been lucky enough to have the most colorful career, and we think it’s interesting for folks to hear about the company’s I’ve worked at and games I made. So, I begin my presentation with, “I teach classes on game design, game development, game publishing, the impact of games on society, as well as the history of games. Let my tell you a little about my own history…”

Last Saturday at the Info Fair we hold after all the presentations, one of the adults who sat in on my presentation came up to me and said, “So, you know about game history. Tell me, what was the first video game company?”

Now that’s an interesting question, because that leads us to also ask “What is a video game company?” and “what is a video game?”

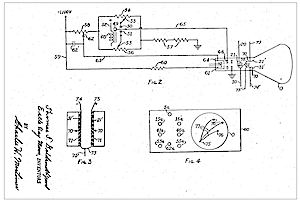

The earliest known electronic game was a missile simulator using analog circuitry and a cathode ray tube developed by Thomas T. Goldsmith and Estle Ray Mann developed in 1947. The player turns a control knob to position the CRT beam on the screen. To the player, the beam appears as a dot, which represents a reticle or scope. The player has a restricted amount of time in which to maneuver the dot so that it overlaps an airplane, and then to fire at the airplane by pressing a button. If the beam’s gun falls within the predefined mechanical coordinates of a target when the user presses the button, then the CRT beam defocuses, simulating an explosion. Goldsmith and Mann filed the patent for their invention, dubbed the Cathode Ray Tube Amusement device, in 1948. The device had no computer, memory, or programming, and some do not consider it a true video game.

The first computer game to display visuals on an actual computer monitor was a version of Tic-tac-toe called OXO. To play OXO, the player would enter input using a rotary telephone controller, and output was displayed on the computer’s 35×16 dot matrix cathode ray tube. The game was developed by Alexander S. Douglas for the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC) computer, which was located at the at the University of Cambridge Mathematical Laboratory in England. However, this game was not sold commercially.

The credit for being the first company to commercially sell a video game of any kind goes to Nutting Associates, which sold a coin-operated video called game Computer Space in August 1971. It was created by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, who would go on to form the historic video game company Atari, creators of Pong and Asteroid, the following year. Unfortunately, the Computer Space was a failure, and Nutting Associates, which had opened as an arcade game manufacturer in 1965, went out of business in 1976.

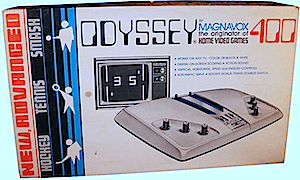

Credit for manufacturing and selling the first very first video game console system goes to electronics company Magnavox. Shortly after its launch in 1917, Magnavox became a major consumer electronics and defense company. It manufactured radios, record players, and eventually televisions. In around 1970, the Magnavox was approached by another electronics company, Sanders Associates, because one of its employees, Ralph Baer, had developed a prototype of a device that could play a number of electronic games on an ordinary television set. Sanders licensed the technology to Magnavox, who sold over 330,000 units of what was called the Magnavox Odyssey, including one to the Mullich family. The system and its games were so popular it triggered the beginning of the home video game console market. (Console inventor Baer, who passed away last month at the age of 92, is now called “the father of video games” and was awarded the National Medal of Technology in 2004.)

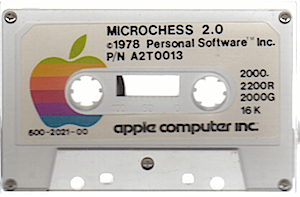

So who was the first video game publisher, independent of a hardware manufacturer? Well, no one can say who was the first personal computer game publisher was, since so many people (such as me while I was in college) could make copies of games they programmed on their home computers and sell them through their local computer retailer. One early contender would be Personal Software, which was founded in 1976 and published the game Microchess that same year. However, the company was not known as a video game publisher as its biggest title was the very first spreadsheet program VisiCalc, which became so successful that the company was renamed VisiCorp in 1982.

Another early video game publisher was Epyx. Founded in November 1978 as Automated Simulations, the company marketed its first title, Starfleet Orion, the following month. After releasing a number of successful action games under the brand Epyx, the company changed its name to its brand name in 1983. In 1989, Epyx discontinued developing computer games, began making only console games, and filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The company became defunct in 1993.

The first independent developer and distributor of video games for gaming consoles was Activision. It was formed in 1979 after a group of game designers at Atari were denied their request for royalties and credit for the games they developed. Dismissed by Atari CEO Ray Kassar as being nothing more than “towel designers”, programmers David Crane, Larry Kaplan, Alan Miller, and Bob Whitehead quit and formed their own company, Activision. Thirty-five years later, Activision remains one of the largest game publishers, with assets of over $14 billion in 2013.

So, which is the first video game company? I’d give that claim to Nuttig Associates, although you could say Sanders Associates, Magnavox, or various other companies, depending upon whether whether you are referring to hardware or software, licensing or selling.