Category Archives: Game Production

When Assembly Language Turned Into Assembly Lines

When I first started my career in game development, programming was much simpler than it is today, and I was able to develop my games in BASIC (Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code), with certain functions such as graphics and AI pathfinding done in assembly language. Games in general were much simpler than today’s games, and I was able to do the game design, art (such as it was) and sounds all by myself.

When I first started my career in game development, programming was much simpler than it is today, and I was able to develop my games in BASIC (Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code), with certain functions such as graphics and AI pathfinding done in assembly language. Games in general were much simpler than today’s games, and I was able to do the game design, art (such as it was) and sounds all by myself.

However, over time, games became larger and larger in scope, and more people were needed to develop a game. The lone developer was replaced by a two- or three-person team, which gave way to a half-dozen member team, which in turn evolved into a twenty, then fifty, and eventually a hundred-person team. Now a major AAA game title might involve over a thousand people, sometimes with several studios and art houses working together.

The production values of games also evolved, and so-called “programmer art” could no longer cut it. Therefore, development teams needed artists who knew how to draw, animators who knew how to animated, writers who knew how to write, and audio engineers who knew how to compose music and create sound effects.

Even these disciplines gave way to sub-disciplines on large-scale projects. The design department might be comprised of a lead designer who oversees system designers, content designers, user interface designers, level designers and writers. The programming department might be lead by a technical director who supervises the engine, physics, artificial intelligence, user interface, audio, multiplayer, and tool programmers. The art director in charge of the art department manages concept artists, texture artists, 3D modelers, riggers, animators, and environmental artists. The sound department might have different professionals specializing in music, sound effects and voice over. Each of these developers need to have their tasks scheduled and coordinated so that everyone works together as a team, and so that responsibility would fall to a producer or director, often assisted by a project coordinator and/or production assistant.

Each of the game’s thousands of assets, whether they be character animations, game levels, or cut scenes, might involve many different developers as the asset goes through conceptualization, design, production and implementation into a team. Creation of these assets involve an assembly-line kind of process, called a pipeline, and an individual developer might spend his or her time on the game just doing one step in this process, over and over again.

Many people who aspire to work on AAA games imagine themselves as having complete creative control over the entire game, but that’s not how major games are made nowadays. If you want to work in the game industry, you need to be able to take satisfaction in simply contributing to the game, even if your role is confined to creating the textures for all the rocks, tweaking all the attributes of the items for sale, or programming in the buttons for all the menus. You will likely be part of an assembly line, and your source of pride needs to be in the entire team’s collective work on the game.

How To Work With A Maestro of Game Music

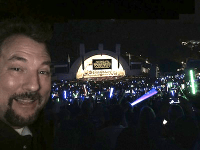

This weekend my wife and I went to the Hollywood Bowl outdoor amphitheater to watch John Williams conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic as they played some of William’s most famous film scores, particularly the ones to the Star Wars films. Of course, light sabers were a very popular souvenir item among the audience, and Star Wars fans waved their swords in time with the rhythm as Williams conducted The Imperial March (also known as Darth Vader’s Theme). The show, called “John Williams: Maestro of the Movies” also included film clips that accompanied some of the pieces Williams performed.

This weekend my wife and I went to the Hollywood Bowl outdoor amphitheater to watch John Williams conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic as they played some of William’s most famous film scores, particularly the ones to the Star Wars films. Of course, light sabers were a very popular souvenir item among the audience, and Star Wars fans waved their swords in time with the rhythm as Williams conducted The Imperial March (also known as Darth Vader’s Theme). The show, called “John Williams: Maestro of the Movies” also included film clips that accompanied some of the pieces Williams performed.

We had attended William’s other performances at the Bowl several times before, but this year fellow film composer David Newman opened the show by conducting the Philharmonic as they played the scores to a number of films, including The Godfather and North By Northwest. Between a couple of the pieces Newman stopped to emphasize how important that a score serve the film in which it plays, becoming an entirely new experience from what it was on the page once it is married to the imagery of the film.

As an example, Newman explained how score composer Bernard Herrmann drew his inspiration for the film’s classic crop duster sequence from a Spanish dance called the Fandango. Because North By Northwest is essentially a chase story, the score is composed with driving, dancing rhythms. And yet, when one watches the film, one thinks not of dancing, but of the protagonist being chased headlong through the music.

Now, this blog is about video games and not films, but some music composers are maestros of both movies and game music. Michael Giacchino, who composes many of J.J. Abrams film scores, began as a game producer for Disney Interactive, thinking he could hire himself to write music for the games he produce. He indeed composed music for the Sega Genesis game Gargoyles, the SNES game Maui Mallard in Cold Shadow and the various console versions of The Lion King. Another composer who has worked in both the game and film industries is John Ottman, who both scores and edits many of Bryan Singer’s films, composed the soundtrack for I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream for me.

One thing that I have learned about both film and game composers is that they are hired onto a project long before the visual part of the project reaches its finished form. The film composer needs to have the music written by the time the final edit of the film is completed, and the composer will conduct the musicians in the recording session while watching the film play onscreen. A game composer is likewise brought onto a project long months before the game is completed, but due to the interactive nature of video games, the game experience is different for each player, and so the composer doesn’t watch someone play the game while the music is recorded. So, even more than with film music, the game composer relies on having a clear understanding from the creative team about what the final experience needs to be like.

When I start working with a music composer, I already have formed at least a preliminary idea of how many musical pieces I will need from him or her. Usually I will want a different musical piece for each of the game’s main mechanics: exploring, building, fighting, and so on. These need to be looping pieces that play continuously through that mechanic’s core loop. Often I will also want variations of each piece for different settings in the game: a desert, a jungle, a city, and so on. As David Newman illustrated in his story about the North by Northwest score, a musical genre can be used in unexpected ways to create an entirely new experienced when paired with the visual element of a movie or game, and so I typically don’t tell my composer what music genre I’m interested in. Instead, I will explain the emotion that the piece should convey: excitement, fear, suspense, and so on, as well as the pacing and context of the game sequence in which it appears. Sometimes the choices the composer makes for the delivered piece surprises me, but when I play it in the game sequence, it usually works.

My job as a game director and designer is to decide the experience I want the player to have, but I leave it to the music experts to figure out how to convey that experience through their compositions. And if our visions successfully synch up, we’ll hopefully have the players perform the mechanics in time with the rhythm.