Category Archives: Game Production

Management Style Differences Between New And Veteran Development Teams

Game development is difficult no matter how seasoned the development team, especially since the more experienced the team, the more likely the game we are developing is more sophisticated and has a larger scope. However, I have managed both veteran and neophyte game development teams, and there is a difference in how I must lead them if I want the project to turn out successfully.

Game development is difficult no matter how seasoned the development team, especially since the more experienced the team, the more likely the game we are developing is more sophisticated and has a larger scope. However, I have managed both veteran and neophyte game development teams, and there is a difference in how I must lead them if I want the project to turn out successfully.

Newer team members need a lot more direction from me on performing their tasks. Having developed many games in my career, I try to keep them from making noob mistakes, such as tackling the easier or more fun parts of game development first rather than taking on the tasks that are on the critical path for developing the schedule on time, such as ensuring that an efficient pipeline is established for developing the art assets, that they figure out a way to resolve technical issues they haven’t dealt with before, and that the core game mechanic is actually fun. Left alone, a neophyte team might start on only the tasks they already know how to do (which are few, considering they are new to game development) or what feels more like they are making a game, such as producing levels, even though they don’t yet understand the game they are making.

As team members get more comfortable with their tasks and roles, I may transition from a director role to more of a coach role, where I still provide team members lots of direction, but much of my time is spent in training them to help them hone their skills. This means that I need to know about their own disciplines and the tools they use, so that I can help them become better at doing their jobs.

Managing a veteran team is different, because they already know their jobs well and (hopefully) learned from past mistakes. Therefore, I give the design, programming and art leads on the team much more leadership responsibility, because they know how to do their jobs much better than I do. My role as a leader is then to be more of a sounding board and a cheerleader for them, while still keeping a watchful eye out for things not going according to plan.

However, I still need to fulfill a support role for them in which I talk with them about the issues and obstacles they are dealing with, but let them decide on the solution and apprising me of their solution — unless it involves a conflict with another lead, in which case I must play the role of King Solomon, deciding which lead has more responsibility for ownership of “the baby”. One thing I do need to look out for, though, is the “not invented here” syndrome, where developers are so confident in their skills that they think they should develop everything from scratch themselves — even if there is a pre-existing solution that will get things working much more quickly.

Once the leads settle into a productive working relationship with each other, then I can focus on more of a delegation role, allowing me to focus on areas beyond the immediate development tasks, such as localization, quality assurance, and marketing.

Regardless of whether I am managing a new or veteran team, it is vital that I gain team member’s respect and trust early on. With neophyte teams, this is so that they gain confidence in themselves and in the project, while with seasoned teams, it helps to keep an arrogant developer from challenging my leadership and trying to perform end-runs around me when he or she has different thoughts about how to do things.

As I said, game development is extraordinarily difficult work, but the job is much easier if you switch up your management style to accommodate the needs of individual teams and team members. Veteran developers still need leadership, but it’s a different kind of leadership — one in which you tap into their talents experience and not limit them with your own.

Tracking Down Game Bugs

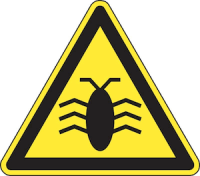

As a development team nears completion of a game’s features and assets (art, audio and text), the game starts to take its final form, but it is likely still rife with errors and problems that we call “bugs”. The term “bug” for a software error came about in 1946 when engineers traced an error in a Mark II computer to a moth trapped in a relay. This bug was carefully removed and taped to the log book. Stemming from the first bug, today we call errors or glitches in a program a bug.

As a development team nears completion of a game’s features and assets (art, audio and text), the game starts to take its final form, but it is likely still rife with errors and problems that we call “bugs”. The term “bug” for a software error came about in 1946 when engineers traced an error in a Mark II computer to a moth trapped in a relay. This bug was carefully removed and taped to the log book. Stemming from the first bug, today we call errors or glitches in a program a bug.

Development teams send off versions of their game to a fresh set of eyes for finding the bugs. These set of eyes belong to the Quality Assurance team, also called “testers”. Testers use check sheets to go through the game and ensure that all the thousands (even millions) of features and assets that were supposed to be implemented are actually there, working as planned.

When a Quality Assurance team reviews a game build and finds bugs, they write up a report for each bug found. Bug reports are generally written in an online database with the following information:

- Bug #: This is automatically generated for each new report. It is much easier to refer to Bug #725 than “you know that problem in the Valhalla level where in the green building in the back where two walls don’t quite fit together properly?”.

- Summary (Headline): A synopsis of the problem.

- Location or Component: Where in the game the problem occurred.

- Description: More detailed information about the bug.

- Expected Result / Actual Result: For when bug is not obvious (for example: after reloading, the gun should have been able to fire 8 shots, but the actual result was that it could only fire 6 shots).

- Steps to reproduce: So that the development team can replicate the bug. Unless a team can recreate a problem and see it for themselves, they may not be able to fix it.

- Reproduction Rate: How frequently the bug occurs. Does it occur all the time (100%)? Have the time (50%)? Is it not repeatable.

- Severity: Bug severity levels are usually categorized as:

- A = (Blocker / Critical) Fatal flaw. Crashes, freezes, can’t finish game.

- B = (Major / Normal) Serious flaw. Features don’t work properly.

- C = (Minor / Trivial) Minor flaw. Glitches in artwork, typos, minor annoyances.

- Priority: Does the problem need to be fixed ASAP? Can it be saved for a patch? (Priority is usually determined by the project’s producer and not the QA team).

This information is sent back to the development team. If they address the issue, they will mark it as FIXED and the QA team will retest and verify the fix when they receive the next build.

The team may also mark a bug as CAN’T REPRODUCE or NEED MORE INFORMATION if they can’t duplicate the problem. Or, if they think the game is working as designed and the QA team just disagreed with the design direction, they may mark the bug as NOT A BUG or WORKS AS DESIGNED. Finally, if the producer decides that this is a minor problem that can ship with the game, it may be marked as WILL NOT FIX.

The bug database is preserved after the product ships so that it can be referred to when making patches and updates to the game.

It is not unusual for thousands of bugs to be found during the course of game testing. And even when using a bug database to track down every single error found, some do slip through the cracks and wind up bugging the customer.