Category Archives: Game History

Games of War

Last Saturday, I gave an online speech of support at Games of War, an international academic conference held at the University of Gdansk (Poland). This academic hybrid (on-site + online) conference was dedicated to exploring the intricate narratives and historical reflections in Ukrainian video games that respond to the Russian 2014/2022 invasion of Ukraine. Below is the text of my speech.

It is an honor to be virtually attending the Games of War international academic conference. I regret not being able to attend in person. I did visit Poland last summer and had a wonderful time in your country.

Of course, here on the second anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it is Ukraine that is in our thoughts now. About three months before the invasion, I attended Games Gathering Kyiv and had the opportunity to become acquainted with Ukraine.

I toured the city and visited the St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery, the Golden Gate, the National Opera house, and the Academic Puppet theater — but what made the biggest impression on me was Independence Square and the Independence Monument, commemorating the independence of Ukraine in 1991. I was moved by the stories of the political protests that had taken place at the square, and I was impressed by the passion and bravery of the people of Ukraine.

During the conference, I got to meet and become friends with many Ukranians. If they were concerned about the Russian army amassing beyond their borders, they didn’t show it. I myself couldn’t imagine that the Russians would actually go through with their plans to invade this wonderful country.

And yet, three months later, the Russians did the unthinkable. The Russian military swarmed the border and fired upon not only military targets, the Russian military deliberately targeted museums, churches and libraries that are important to the Ukrainian people.In the first months after the invasion the Russian army looted museums, stole art and destroyed churches with missiles and tank shells.

I feared for some of the places I had visited in Kyiv, but that was nothing compared to the tragic news that some of the friends I made in Ukraine had lost their homes… or their lives… to the Russian invaders. But the Ukranians proved not to be easily dominated, and their hearts have proved stronger than the Russian shells and rockets.

Still, it has been two years of trials and anguish for the Ukrainian people, and they have never been far from my thoughts. One encouraging bit of news I received from a Ukrainian journalist whom I had met during my visit was that playing Heroes of Might & Magic III had provided them with some relief during this difficult time.

Now, one might scoff at the notion that something as frivolous as playing a game could have any impact when something as serious as war was happening around you.

Yet Johan Huizinga, the Dutch historian who studied the play element of culture and society in his book Homo Ludens, said, “Play cannot be denied. You can deny, if you like, nearly all abstractions: justice, beauty, truth, goodness, mind, God. You can deny seriousness, but not play.”

Huizinga suggested that play is primary to and a necessary condition of the generation of culture. And I think that it is a far stronger force than that of the Russian weaponry attempting to destroy it.

But play is not just important for culture, it is also important to us as individuals. As the German playwright Friedrich Schiller said, ““Man only plays when (in the full meaning of the word) he is a man, and he is only completely a man when he plays.” We are not completely human without play; we need play to be complete — especially in inhuman times like these.

But what is it about games that make us complete? For that, I’ll turn to game designer Jane McGonigal. In her 2010 Ted Talk “Gaming Can Make For A Better World”, McGonigal observed that it is said that one needs to spend 10,000 hours doing something to become an expert at it. Well, gamers easily spend more than 10,000 hours of their lives playing games, so what is it that they are becoming experts at.

Here is what she determined.

Gamers develop what she calls “urgent optimism”, the desire to act immediately to tackle an obstacle, combined with the belief that they have a reasonable hope of success. Rather than being discouraged by failure, they get up and continue to try again until they succeed.

Gamers are also optimized as human beings to do hard and meaningful work. Engaged in what McGonigal calls “blissful productivity”, gamers are willing to work hard all the time if given the right type of work to do. Gamers will stick with a problem for as long as it takes.

When gamers play games together, they build up bonds of trust and cooperation. In the social fabric of gaming, they build stronger social relationships and are inspired to collaborate and cooperate.

Gamers also love to be attached to awe-inspiring missions, to save the world around them. They are motivated to do things that matter.

Urgent optimism, blissful productivity, social fabric, and epic meaning — aren’t these all things that will make people resilient at a time of war. I think we need games now more than ever.

But what of game developers? What motivates them to make games? In my own case, I got into game development as an outlet for creative expression. The first hit game I made, The Prisoner, was a metaphor for things I wanted to say about standing up to authority and maintaining your individuality when all of society is pressuring you to be obedient and submissive.

In most of the games I’ve made since, I’ve tried to share something I’ve learned or something I’ve cared about. Games are my Independence Square for expressing my thoughts and opinions.

So, I find it not at all surprising that many Ukrainian game developers and their supporters have developed games inspired by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. To my fellow game developers, I say:

Use our medium to tell inspiring, epic stories of tragedy and triumph.

Make missions that matter in your strategy games. There is a world to save.

Push your players to the limit. Players love to be challenged, but you can challenge their hearts, as well as their reflexes and minds.

And seek out collaborators to help you tell your story and theirs. Game development is a team effort, and if you need help in developing your game, there are others out there who would love to be a part of something meaningful.

As for the academics and researchers attending this conference, you need no reminders that Ukrainians have managed to find a remarkable balance between war, work, and life. The rest of us have much to learn from them.

In particular, I am eager to find out what you do learn from looking through the lens of the games of war they have developed and what understanding you gain from how they have portrayed and interpreted the historical events unfolding around them. I look forward to hearing the results of your discussions today about how digital storytelling has intersected with history and conflict.

The Russian invasion may have been a military attempt to erase Ukraine’s history, culture and heritage, but with the good work that the Ukranians continue to do, and with conferences like this to shine a light on it, it is Ukraine who will be triumphant in the end.

Commemorating SpaceWar! And Its Pioneering Developers

My manager at a game publishing company I worked at years ago came out of the film industry, and as I was discussing some of the early videogames that had influenced me, he interrupted me to say that he had no idea that gamers had such a sense of history. Just as film buffs love classic movies, many of us gamers love so-called retrogames. We are drawn to them not just out of nostalgia for different eras, but also out of appreciation for their originality, inventiveness, and elegant simplicity. Also, those of us who know our game history realize that game developers reach the heights that they do only because they are, to use a well-worn but appropriate phrase, standing on the shoulders of giants.

My manager at a game publishing company I worked at years ago came out of the film industry, and as I was discussing some of the early videogames that had influenced me, he interrupted me to say that he had no idea that gamers had such a sense of history. Just as film buffs love classic movies, many of us gamers love so-called retrogames. We are drawn to them not just out of nostalgia for different eras, but also out of appreciation for their originality, inventiveness, and elegant simplicity. Also, those of us who know our game history realize that game developers reach the heights that they do only because they are, to use a well-worn but appropriate phrase, standing on the shoulders of giants.

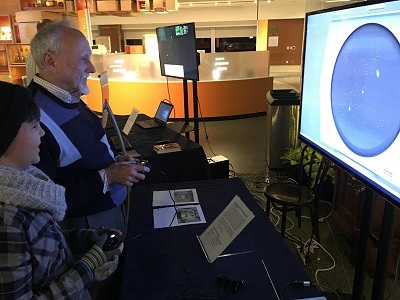

And so last week I was thrilled to be invited to attend Innovative Lives: The Pioneers of Spacewar!, an event honoring the developers of a 1962 video game that helped launch our industry, hosted by the Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington. DC. The event brought together, for the very first time in sixty years, seven of the game’s remaining developers — Dan Edwards, Martin (“Shag”) Graetz, Steven Piner, Steve (“Slug”) Russell, Peter Samson, Robert Saunders and Wayne Wiitanen — to discuss the development of their influential video game.

And so last week I was thrilled to be invited to attend Innovative Lives: The Pioneers of Spacewar!, an event honoring the developers of a 1962 video game that helped launch our industry, hosted by the Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington. DC. The event brought together, for the very first time in sixty years, seven of the game’s remaining developers — Dan Edwards, Martin (“Shag”) Graetz, Steven Piner, Steve (“Slug”) Russell, Peter Samson, Robert Saunders and Wayne Wiitanen — to discuss the development of their influential video game.

During a cocktail reception before the panel discussion, Lemelson Center director Arthur Daemmrich explained to me how fortunate it was that many of the pioneers of the video game industry were still alive to be interviewed and have their memories and insights recorded for posterity, and that was part of the impetus for hosting this event. Such first-hand recollections allow us to understand the personalities, technologies and social forces that came together to make interactive entertainment one of the most successful industries of all time.

When it was time for the honorees take the stage, I was pleasantly surprised how energetic and enthusiastic these seven octogenarians were. During the panel, moderated by Bethesda founder Christopher Weaver, they recalled how, in 1961, they were all either students or employees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) had donated PDP-1 minicomputer for educational purposes to complement the older TX-0 in MIT Electrical Engineering Department. Even before it arrived, they began brainstorming ideas for programs that would demonstrate the new computer’s capabilities in a compelling way.

When it was time for the honorees take the stage, I was pleasantly surprised how energetic and enthusiastic these seven octogenarians were. During the panel, moderated by Bethesda founder Christopher Weaver, they recalled how, in 1961, they were all either students or employees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) had donated PDP-1 minicomputer for educational purposes to complement the older TX-0 in MIT Electrical Engineering Department. Even before it arrived, they began brainstorming ideas for programs that would demonstrate the new computer’s capabilities in a compelling way.

It was Russell, Graetz, and Wiitanen who came up with the idea for Spacewar! They wanted to show off the PDP-1’s display capabilities and thought that making a two-dimensional maneuvering program would be a good approach, and being science fiction enthusiasts, decided that the obvious thing to do was spaceships. Professor Jack Dennis, who was responsible for the PDP-1, thought this was a great educational opportunity for the students. In exchange for giving them time to make their game, he asked them to port the TX-O’s operating system to the PDP-1 over a 3-day weekend. His only other requirement was that they not break the computer.

Fortunately, they found the PDP-1 easy to program. Also, two of the students were members of the Tech Model Railroad Club and their knowledge of track relays and circuits helped them to devise the game’s logic. They decided to have the gameplay involve two monochrome spaceships< called "the needle" and "the wedge", attempting to shoot torpedoes at one another while maneuvering on a two-dimensional plane in the gravity well of a star, The ships followed Newtonian physics, remaining in motion even when the player is not accelerating, though the ships can rotate at a constant rate without inertia. The sun in the center of the screen was created as an element the player couldn't control; it helped make SpaceWar! a game of skill.

Fortunately, they found the PDP-1 easy to program. Also, two of the students were members of the Tech Model Railroad Club and their knowledge of track relays and circuits helped them to devise the game’s logic. They decided to have the gameplay involve two monochrome spaceships< called "the needle" and "the wedge", attempting to shoot torpedoes at one another while maneuvering on a two-dimensional plane in the gravity well of a star, The ships followed Newtonian physics, remaining in motion even when the player is not accelerating, though the ships can rotate at a constant rate without inertia. The sun in the center of the screen was created as an element the player couldn't control; it helped make SpaceWar! a game of skill.

To make Spacewar! easier for beginning players who founded themselves surrounded by torpedoes, the team added a hyperspace jump feature that players could use to vanish from tough situations, but to keep the feature from being abused, they had the ship reappear at a random position — possibly even a more dangerous one. They also balanced the skill of skilled players by limiting the amount of fuel and torpedoes available to them.

Because of the PDP-1’s limited processing power, the team found that the computer could not have every game element obey real-world physics and update the screen at an acceptable rate. So they decided that the torpedoes fired by the ships would not be affected by the gravitational pull of the star (they were “photon torpedoes”, one of the panelists jokingly explained). However, the team did allow for the game’s starfield to be based on a real star chart, with the star positions modified based on the seasons.

Spacewar! did not work immediately because Russell was “lazy” and didn’t want to write a sine and cosine function for the game. The team eventually got functions from someone else, and Russell emulated these for the game to make it work correctly. The final game worked so well that DEC used it to test its other computers to ensure they were operating at proper performance rates.

Spacewar! was extremely popular in the university programming community in the 1960s. The MIT team made the game public, and other students recreated it on the minicomputer and mainframe computers of the time. Computer scientist Alan Kay noted that “the game of Spacewar! blossoms spontaneously wherever there is a graphics display connected to a computer.” By 1972 the game was well-known enough in the programming community that Rolling Stone sponsored the “Intergalactic Spacewar! Olympics.”

In the early 1970s, Spacewar! migrated from large computer systems to a commercial setting as it formed the basis for the first two coin-operated video games. Some of the games that were influenced by Spacewar! include Computer Space, developed by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, which would become the first commercially sold arcade video game and the first widely available video game of any kind, as well as Orbitwar (1974), Space Wars (1977), Space War (1978) and Asteroids (1979).

It should come as no surprise that at the conclusion of the panel, Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences president Meggan Scavio presented these developers with the organization’s Pioneer Award, honoring individuals whose career-spanning work has helped shape and define the interactive entertainment industry through the creation of a technological approach or the introduction of a new genre. As the Spacewar! creators became the AIAS’ ninth through fifteenth Pioneer Award recipients, we in the audience — which included such other video game pioneers as Ultima creator Richard Garriott, Deus Ex creator Warren Spector, Zork creator Dave Lebling, and Defender creator Eugene Jarvis — gave them a rousing standing ovation, for the game industry would probably not be what it is today without their contributions.